A design research report from Stanford’s Justice By Design: Eviction class in Winter 2022

Why are eviction prevention resources like websites, mediation programs, legal aid services, and hotlines underutilized? Our team interviewed tenants from across the country about their experiences with evictions, getting help (or not), and their ideas for what would be better.

This report details 7 main barriers that tenants reported, that legal and community organizations should focus on when improving eviction prevention systems.

- Informal Evictions where landlords pressured tenants to leave without going to court — and thus also not activating the eviction prevention service network

- Eviction Warning & Court Notices are complex, intimidating, and dis-empowering

- Court is Fearsome and Inaccessible, so people would rather avoid it — both for rational and strategic goals, as well as the stress and intimidation of it

- Wanting to avoid a ‘Fight’, with instead a focus on getting help and services (or just wanting this problem to end)— not pursuing an adversarial response against their landlord

- High Stress during the problem time, so much that people who normally are resourceful and proactive in finding help for their problems were rendered unable to seek out help or be strategic

- The burden of accessing services, so that even if a person started trying to get legal or financial help, the time and work required was too much to make them usable or actionable.

- Difficulty in sharing one’s hard-won expertise with peers, even when a tenant has figured out what to do (and not to do) to access resources and prevent an eviction — and they want to share this knowledge with others — there is no clear pathway to do this peer-to-peer education

This report is by the class team Trevor Byrne, Emma Dolan, Jordan Payne, Alexandra Reeves, Amy Zhai — along with the teaching team Nora Al Haider, and Margaret Hagan. This report was also published on our Legal Design & Innovation Medium publication.

- How our class did this user research

- Big Takeaways on Tenant Barriers & Needs in Eviction Prevention

- Key Problems with the eviction system, from the interviews

- Problem 1: Renters caught in Informal Evictions — where no service groups are connecting with them

- Problem 2: Eviction Notices are Complex & Inaccessible

- Problem 3: Fear of court and court inaccessibility

- Problem 4: Fear of “fighting,” desire for help

- Problem 5: High stress in the Eviction Journey

- Problem 6: Accessing Services is Burdensome

- Problem 7: A desire — but no outlet — to help others

- Eviction Prevention Ideas, Based on Tenant’s Experiences Tell us about

- Key Opportunities for Courts, Local Governments, and Legal Help groups to prevent evictions

- Next Steps for Tenants & Eviction Prevention

As the eviction crisis spreads throughout the United States, there is an access to justice paradox that has emerged.

More and more groups — legal aid, court self-help centers, city governments, emergency rent programs, and legal help websites — are trying to get help out to tenants who are at risk of eviction. These groups have legal guidance, rental assistance, and mediation resources to help tenants pay back their rent, make agreements with their landlords, or fight back against eviction in court.

But there’s a disconnect. Many tenants never reach out for help. They don’t call these groups, visit their offices, or go to their websites. Or they may start out to seek help, but then fall off during the process. They cannot ‘complete their justice journey’. They’re not able to assert their rights, use free services, or protect themselves from a forced move.

So, what are the barriers that are stopping renters from seeking or using legal help & other services, when they are at risk of forced displacement from their homes — and all the collateral consequences that come with an eviction?

That was the driving question of our Winter 2022 Stanford Law School class, Justice By Design: Eviction. We have taught versions of this class throughout the past few years as a ‘policy lab’ class at SLS. This time we partnered again with the NAACP as our policy lab partner, because they also are interested in engaging more tenants with legal and community help when they’re at risk of forced displacement or eviction.

In this Winter 2022 class, our focus was talking with tenants who had eviction experiences. From their stories, through deep, qualitative interviews, our goal was to identify these barriers to seeking help, as well as to spot opportunities for more effective outreach and interventions to help tenants at risk.

This report summarizes what we heard from our tenant interviews, as well as the interventions and strategies the class identified to encourage more tenants to increase their ability to defend themselves, use services, and avoided the harmful consequences of an eviction.

How our class did this user research

Our class team had students from all over Stanford, who were interested in learning more about eviction, housing policy, public interest technology, and justice system reform. Justice By Design: Eviction was a 9-week class, listed in the Law School, but open to undergraduates and graduates from across the university.

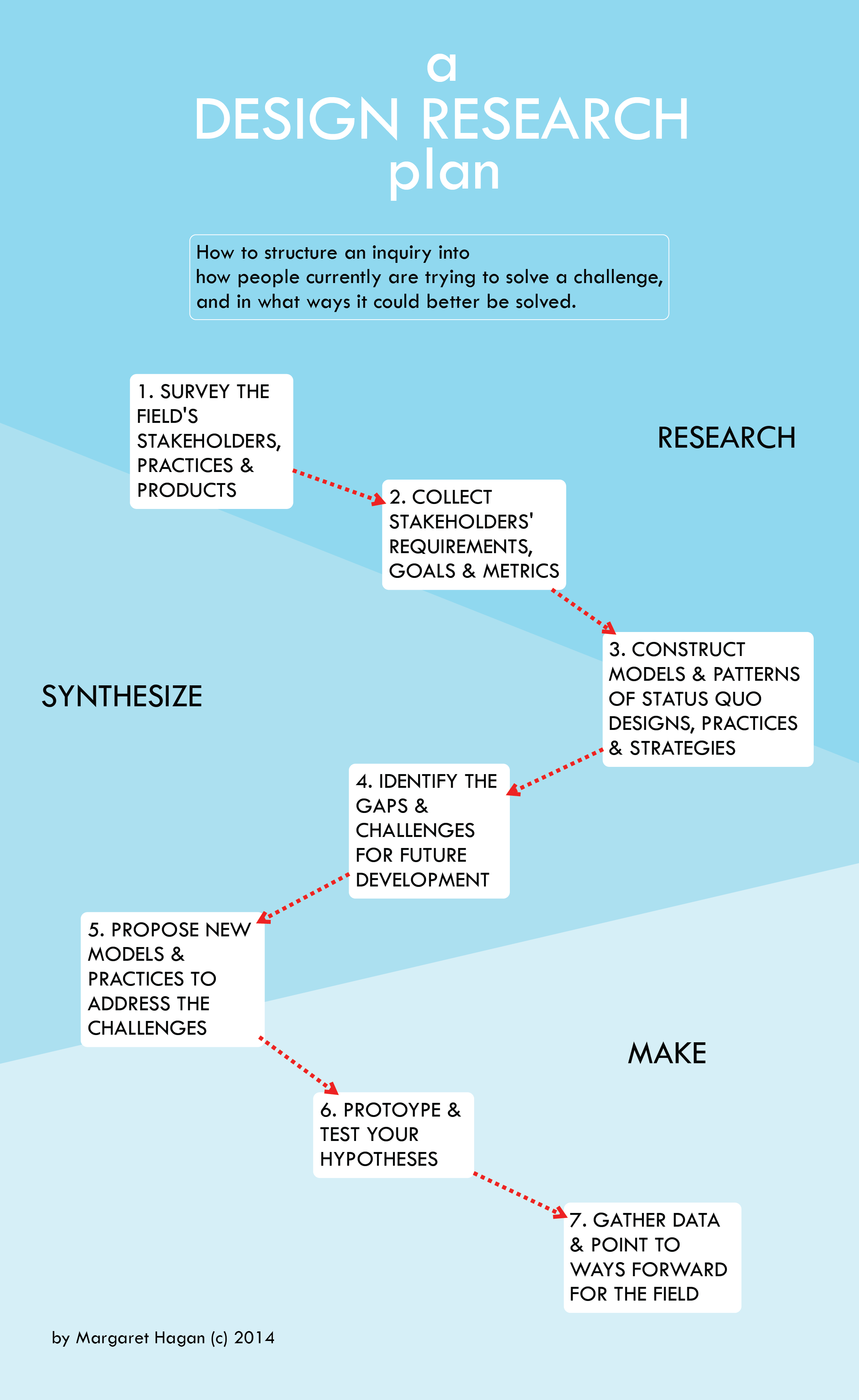

After introductory weeks that taught the students about the basics of the eviction crisis and how housing courts work, then our teaching team prepared the students for qualitative interviews with renters who had experiences with eviction. This included prep on ethical design work and engagement with the community, as well as a primer on the past eviction prevention work done in our class & Legal Design Lab.

Our teaching team had recruited renters through social media ads that asked, “Do you have experience with eviction? Do you want to speak to our university team about your experiences and ideas?” We also offered Amazon gift cards in compensation for being interviewed.

The students, in pairs or teams of 3, interviewed 16 tenants, navigators, and landlords across the country. The goal of the interviews was to learn from the tenants’ experiences, identify their barriers to participating in the justice system, and hear their ideas. We asked general questions about their experiences with eviction, their experiences with seeking out help, and their ideas for change.

After conducting the interviews, then the student teams synthesized interviews by creating personas, user journeys, and visual representations of salient moments gleaned from the interviews. They also analyzed the various stories and proposals to identify commonalities that point to pervasive issues and suggest potential reforms.

Big Takeaways on Tenant Barriers & Needs in Eviction Prevention

When we talk about Access to Justice in evictions for tenants, often the primary recommendation is to provide a Right to Counsel — a guaranteed free lawyer for anyone who reaches out for help with an eviction lawsuit. What we found, though, is that the A2J problem and needs are more complicated than that.

In the interviews, we heard repeatedly from renters:

- We don’t actually want to go to court or fight this. We just want a better way to move past this problem with the landlord or threat of eviction. These tenants prefer not to get a lawyer or do anything to make the situation more adversarial or more formal. They want to avoid the stress, cost, and fight of entering the justice system. Some people reasoned that engaging with lawyers or courts would make the whole experience more destructive for their family and their own mental health. Or, they chose to focus on making a plan of action focused more on getting money and housing choices to get a stable transition to a new living situation. If they have limited bandwidth and time, they choose planning-their-move rather than fighting-in-the-legal-system.

- The whole thing happened so fast & I was so stressed, that I couldn’t even reach out for help. This theme came up repeatedly. In some cases it was based on a sense of being paralyzed with stress, feeling overwhelmed, and not wanting to address the problem they were dealing with. In other cases, it was linked to an unfamiliarity with how to get help, who could help, or how to even talk about what was happening. The result of these situations was that the tenant doesn’t seek help. They’re not telling people that they’re in a problem — they’re not searching online — they’re not calling groups that could help them.

- Landlords could be a key channel of information, but right now they aren’t. Even for tenants who had relatively good relationships with their landlord, they weren’t able to get information about their rights, processes, or services from their landlord. From an outsider’s perspective, it would seem that the landlord should be the key provider of key information: they are a business-owner, with repeat relationships, and obligations to provide quality and safe housing. But right now most landlords don’t seem to be aware of the law around how tenancies can and should be ended, when they are allowed to evict, what services are available to repair relationships or assist with rent, or other key information to prevent forced moves & evictions.

- I figured that I made the mistake, so I just had to leave. Many people had problems paying their rent, and this was the instigation of their eviction. They knew they weren’t able to make their full rent, and so assumed they were left with only one path: to just move out. Because it was ‘their mistake’, they didn’t feel they had any right to ask the landlord for a renegotiation, settlement, or other kind of way to stay in their home. They also didn’t think to reach out for services that could help them make up the rent they owed, or find legal strategies to stay.

Key Problems with the eviction system, from the interviews

The students went through the experiences of the interviewed tenants, to spot where the system is breaking down. When did people not know about their rights as a tenant? When were they not able to participate effectively in the justice system? When were they feeling stressed, fearful, and desperate? When were they being harmed because they didn’t know about help — or they didn’t feel they could access it?

We identified 7 common problem areas that tenants were dealing with. These all constitute barriers to finding and accessing help, that could help the tenant on their ‘justice journey’ to getting procedural and substantive justice in their housing problem. Some of these barriers are psychological perceptions or situations; others are structural problems with how the justice system, legal services, and financial services are set up. Many of them are a mixture of both — a barrier that combines the burdens of the person’s individual situation that make it hard for them to seek out help, along with institutional features or legacies that make the system difficult to access.

- Informal Evictions where landlords pressured tenants to leave without going to court — and thus also not activating the eviction prevention service network

- Eviction Warning & Court Notices are complex, intimidating, and dis-empowering

- Court is Fearsome and Inaccessible, so people would rather avoid it — both for rational and strategic goals, as well as the stress and intimidation of it

- Wanting to avoid a ‘Fight’, with instead a focus on getting help and services (or just wanting this problem to end)— not pursuing an adversarial response against their landlord

- High Stress during the problem time, so much that people who normally are resourceful and proactive in finding help for their problems were rendered unable to seek out help or be strategic

- The burden of accessing services, so that even if a person started trying to get legal or financial help, the time and work required was too much to make them usable or actionable.

- Difficulty in sharing one’s hard-won expertise with peers, even when a tenant has figured out what to do (and not to do) to access resources and prevent an eviction — and they want to share this knowledge with others — there is no clear pathway to do this peer-to-peer education

We have more details and example tenant stories for each of these 7 problem areas. These all include anonymized details from the interviews we conducted with tenants across the US.

Problem 1: Renters caught in Informal Evictions — where no service groups are connecting with them

Many tenants described falling behind on rent and feeling that they had to move out, even before they had been served with any formal eviction documents. Landlords often don’t follow proper notice procedures for eviction, telling their tenants to pay what they owe or start planning to move out. Considering a pervasive fear of the legal system, as discussed below, it is difficult to imagine tenants being empowered to hold their landlords accountable for breaking the law.

Especially for tenants behind on rent, many lack a feeling of agency to look for resources. They assume that because they are behind on rent, they will not have any recourse to resist displacement.

The fact that many evictions occur informally presents unique challenges for policy implementation. Many eviction reforms are centered on the court process. The assumption baked into these programs is that services should be unlocked once a landlord goes to court and files an action against a tenant.

But legal and court reforms will not affect the experiences of those evicted extralegally. The landlord doesn’t go to the court, there is no official record of the possible eviction, and thus the services &the policies are never triggered. The tenant (and the landlord) don’t know that these financial, legal, and mediation services even exist.

These tenants’ experiences highlight the need for empowering interventions that occur before the eviction experience. Tenants (and landlords) need to know of their rights and resources before a housing scare occurs. Service groups need to find ways to connect with people who are not in the official court records. Any intervention that does not reach clients pre-eviction may be too late.

John’s Story: Informal Eviction even in a city full of resources

John (we have changed his name) was informally evicted from his home in San Francisco. Due to local tenant protections, John very likely could have received legal aid — if he knew where to look. But John was evicted informally; he was told to vacate by his landlord, without being provided any proper legal notice.

John was recovering from injuries he sustained during an accident, so he did not feel that he had the ability to look for any financial or legal resources. Unable to make up the rent he owed, John and his family had to move out. They were able to live temporarily with friends and family until they found a new place to live.

John’s story is a prime example of how even when robust legal or financial resources exist, these resources provide no recourse to informally evicted tenants who lack awareness of their options. Ensuring that tenants are informed of their rights and resources before a crisis occurs is critical.

Problem 2: Eviction Notices are Complex & Inaccessible

Receiving a Notice to Quit or an eviction summons could be a potential point of intervention. These notices ideally would tell tenants:

- why they are receiving the notice;

- how they can respond to the notice; and

- resources they can seek if they need assistance.

Formal eviction notices are far from this ideal. To most tenants, they appear to be warnings that they need to leave, rather than indicators that they have options as part of an ongoing process.

Notices tend to be written in confusing English, and are often not served in foreign languages.

Some states have attempted to simplify eviction notices. In Massachusetts, for example, an eviction summons gives the tenant a court date. Getting to court can be difficult, but being given a date and location seems easier to comply with than the requirement of making an official legal filing.

Greater Boston Legal Services has a free online service that prompts tenants with questions to answer in plain English, then creates a form that tenants can use in Housing Court to help them defend themselves. Instead of forcing people to file an official Answer, giving tenants the option to fill out an online form where they can explain their situation could be much more tenant-friendly.

The Problem of Bureaucratized Landlord-Tenant Communications

We also learned that the landlord-tenant relationship is becoming increasingly bureaucratized. Many tenants live not under mom-and-pop landlords, but rather under large, impersonal property management companies. These companies can churn out Notices to Quit summarily after tenants fall behind on rent — even if they fall behind for just a few days. Tenants feel slighted by this impersonal process; they are asked to vacate without anyone checking in on them or trying to work things out informally.

Property management companies provide an interesting wrinkle in how we think about policy implementation. Because their systems are bureaucratized (and may be less personally antagonistic toward non-paying tenants), it may be simpler for them to implement positive changes — like attaching an NAACP Navigator flier whenever they serve a Notice to Quit.

Linda’s Story: How a Notice Confuses rather than Empowers

Linda works as a case manager for people affected by COVID, and her work includes assisting people through eviction scares. She is completely knowledgeable of all the resources available to tenants in her home state of Colorado. Because she lives under an impersonal property management company, she received a Notice to Quit after falling behind on rent for three days.

Having lived in her home for some time without any issues, Linda was shocked and offended that the company would try to kick her out after being behind for just three days. And even though she knows the law, she reported that her ability to comprehend her rights was compromised when she received her notice — she started to second-guess her own knowledge.

Linda acknowledges that if she did not have her specialized background knowledge, the notice would likely have prompted her to leave.

Problem 3: Fear of court and court inaccessibility

Most tenants we interviewed never really pictured their eviction scare as a legal issue. For most who sought recourse, their emphasis was on finding enough money to pay. Some tenants expressed uncertainty about what, if any, legal resources were available to them. Certain tenants expressed that they did not qualify for legal aid, yet they could not independently afford legal assistance.

Beyond the problem of access to legal advice, many tenants expressed broad skepticism about participating in court. There is a shared understanding that court is a protracted, exhausting endeavor. Having to balance that experience with a family, a job, and other obligations is challenging and sometimes impossible. For some, going to court does not feel worth the risk of losing time for their other commitments, potentially having the black mark of a formal eviction on their record, exposing their children to a courthouse, or going against their landlord — who they identify as having more power within the system.

Any interventions that focus on the legal process of eviction must consider the fact that many tenants are evicted informally, and that even tenants with the opportunity to go to court choose to avoid the process of legal resistance. If interventions are designed to make court more tenant-friendly and more feasible to navigate, these changes need to be communicated to tenants to change a widespread negative perception of the legal system.

Linda’s Story: Going to Court Isn’t a Viable Option

As discussed above, Linda works with people being evicted, so she is very aware of tenant resources and legal rights. When she faced her own eviction scare, however, she did not see the court as a viable option, and she instead opted for finding financial assistance.

Certainly, going to court could yield a positive result, but the prospect of being formally evicted and having that on her permanent record was too risky. The fact that even someone as knowledgeable as Linda was scared of the courts should be highly-telling to policy-makers.

Problem 4: Fear of “fighting,” desire for help

Related to the fear of court, tenants generally had overall apprehension at the thought of “fighting for their rights” or resisting. Due to the high stress of eviction, as well as the numerous obligations many tenants have to balance, the notion of resisting doesn’t always seem feasible or attractive. Most tenants focused not on resisting, but rather on getting some assistance and moving on with their lives.

Many eviction prevention policies place a heavy emphasis on lawyering, and encouraging tenants to resist through the various legal defenses they can raise. But to better meet tenants’ needs and desires, non-legal help (like the Navigators) may be a preferable intervention. Several tenants sought out rental assistance, but not legal assistance, suggesting that tenants may disfavor interventions that are seen as overly combative. There was also a widespread consensus that rental assistance was more accessible than legal services.

The tenants we spoke with seem to disfavor legal interventions, policy that focuses on strengthening the legal backbone of eviction defense may fail to affect tenants who are simply seeking to move on as soon as possible and reach a place of stability. A good area for further inquiry would be asking tenants how they feel about lawyers generally as a resource. Would they be comfortable reaching out to a lawyer, or do they feel more comfortable reaching out to non-lawyer advocates?

One organization that focuses on prevention, rather than resistance, is HomeStart in Boston. HomeStart’s first line of defense in eviction prevention is a rental assistance payment program that seeks to help tenants halt the eviction process and pay back rent. HomeStart also has non-lawyer advocates who accompany clients to Housing Court, where they assist in negotiating feasible payment plans with landlords. HomeStart’s focus on holistic services and stability, rather than legal defense, may feel more accessible and comforting to tenants.

Ken’s Story: I’d Rather Get Services than Engage in a Legal Fight

Ken fell behind on rent and was served with an eviction notice after failing to resolve the issue informally with his landlord. Ken decided not to seek out legal aid or resist the eviction. He figured that the legal process would be too expensive. Plus, because he was behind on rent, he believed that he had no chance of asserting a legal defense.

Ken was more comfortable reaching out to Southwest Behavioral and Health Services, where he was placed with a caseworker. Ken had a great experience seeking out holistic services. He was able to secure financial assistance to find a new home, and his caseworker also assisted him in filling out housing assistance applications. Ken now has Section 8 housing.

Problem 5: High stress in the Eviction Journey

Several tenants communicated that they might have the ability to search for resources if the housing problems were happening to someone else, but that their ability to problem-solve was significantly clouded by their high levels of stress. Tenants have to balance family obligations, work, health, and other life stressors. The emotional turmoil of housing insecurity means that it is often not feasible to seek out proper channels of assistance under these circumstances.

The reality of eviction is that even the most resourceful of tenants are often unable to figure out where to go to get help. Even if tenants know their rights, it may be asking too much for tenants undergoing this traumatizing process to resist.

Perhaps interventions should therefore be centered around providing tenants the assistance of a third party, like a Navigator, who can take on the burden of finding resources. In other words, interventions that focus solely on empowerment and self-advocacy may fall short in these situations of heightened vulnerability.

Problem 6: Accessing Services is Burdensome

Aside from the problems of tenants not knowing about services — there are problems for those who have taken that step on their justice journey, are trying to get help, and still it is not solving their problem.

Many tenants who attempted to secure financial or legal help struggled to actually make it work.

One tenant, Darlene, actually sought legal aid, but the offices she contacted were unresponsive due to overwhelming demand. Darlene became frustrated, and ultimately stopped trying to seek out legal aid when the stress of her impending eviction became overwhelming.

Another tenant, Linda, was frustrated by the ERAP process. Her ERAP payment would take months to process, but she had very little time to pay the rent she owed. Linda ended up having to borrow from friends and family to stay in her home. Multiple tenants expressed a desire for an easy-to-access, uniform service for rental assistance.

Problem 7: A desire — but no outlet — to help others

One of the most unfortunate ironies of eviction is that it is such a widely shared experience in some communities, yet the experience of being evicted is completely isolating. Many tenants who have experienced an eviction scare gain practical knowledge about best practices, but that knowledge is lost if not shared with others.

Several tenants expressed gratitude that they were able to share their eviction stories, and were hopeful that the information they relayed would help others in similar situations. A surprising number of tenants showed an interest in becoming more formally involved in eviction prevention and attending events to share their experiences.

Being evicted is a disempowering experience, and we heard tenants express that talking about their experiences was helpful. People seemed to appreciate having their voices heard, even if just for a brief interview. Eviction is a community problem, not an individual problem, so interventions should seek to integrate larger communities.

Jen’s Story: I have hard-won experience — how can it help others?

Jen has gone through eviction several times. She experienced manipulation and invasions of privacy when she had unofficial housing contracts.

After being in these two situations in which she was taken advantage of by landlords, she now feels empowered to speak up for others in the Vietnamese community. She knows many people are facing the same issues, and she wants to use her voice to stand up for her community. During our interview, she asked if there are ways that she could help spread key information & get more help to people who are in situations like hers.

Eviction Prevention Ideas, Based on Tenant’s Experiences Tell us about

Based on the conversations we had with tenants across the country, the class identified 3 key takeaways from the eviction process that are integral to any user-centered solution. If services and policies are going to reach tenants, engage them, and help them solve their key problems — then they should be designed with these guiding principles in mind.

Eviction Prevention Principle 1: Early, Preventative Communication is key

If a service is going to reach people & be used by them — then the service provider needs to already be in communication with them before the landlord-tenant crisis boils up to possible eviction.

That means that legal aid, court, ERAP, and other groups need to be building a relationship with tenants and landlords as early as possible.

For each tenant that we spoke to, communication during the eviction crisis — primarily between tenants and landlords, though also with families, employers, court employees, judges, government officials, and more — seemed to fail. The tight timelines of evictions can jam already busy communications lines, and even a day of unresponsiveness or a misunderstood court order can be the difference between a family staying in their home with their back rent paid, or living in temporary housing while struggling to find a new home.

Facilitating clear communication throughout the eviction process will be key to ensuring fair, mutually beneficial outcomes. And often that means building up a communication channel or relationship before a person is in a highly stressful timeline.

Eviction Prevention Principle 2: Isolation is disastrous, and there is power in peer-to-peer support

Almost each conversation that we conducted with evicted tenants revealed the overwhelming sense of isolation that endured throughout their eviction processes.

With no one to turn to, tenants were consistently forced to adopt short-term, fight-or-flight thinking to best cope with the situation at hand. This often meant accepting unlawful evictions, or not knowing who to call to access the legal aid they were eligible for.

When tenants have no support through the eviction process, they must consistently make decisions out of necessity. Supported, connected tenants, on the other hand, are much more likely to fight for their rights and reach mutually beneficial solutions.

This points to solutions that build up community networks, issue-spotting bots, peer-to-peer navigation — -and other solutions that can help identify when someone is going through an eviction crisis and be a supportive, accessible, low-burden way to find resources and make strategic choices.

Considering that many tenants have hard-won expertise in navigating eviction choices and services — can there be initiatives that unleash peer-to-peer support in communities? This can overcome isolation & build community knowledge of what to do.

Eviction Prevention Principle 3: Tackle the Low Awareness of Help Resources

Right now, tenants and landlords have very low awareness that groups can help them with their problems or evictions. They don’t know that there are legal aid groups or ERAP services.

Tenants are nearly universally lost when they receive an eviction notice or are made aware of an informal eviction process. Up to the point of eviction, they have received no education on how to manage an eviction process or their rights as a tenant. Generally, once the eviction process has begun, eviction education is almost useless — dealing with a current landlord, in addition to working to find a suitable new home, is stressful enough.

Even in cities with robust tenant services and resources, like San Francisco, tenants still do not know who to reach out to when they are served with an eviction notice, and are thus not able to make use of the available services. Tenants must be informed enough to know where to turn, even if this is just knowing an urgent, non-emergency number, like 311.

How do we get more people to know what to do when facing eviction? Ideally, there can be public education campaigns like over social media, news, schools, and other places. And there can be memorable, easy-to-access channels to reach out for help.

Key Opportunities for Courts, Local Governments, and Legal Help groups to prevent evictions

Inspired by current policy solutions and pilots across the US, we used these key takeaways from tenant interviews to determine three potential opportunities for intervention in the current eviction landscape:

Establishing Mandatory, Early Mediation

Currently, almost all jurisdictions see eviction cases go straight to the courtroom. Tenants often choose to forgo their right to a trial out of intimidation. Or, they don’t want the stress of having an adversarial ‘fight’ at the same time as they are juggling a possible housing move.

With mandated mediation, tenants have the opportunity to meet the landlord on a more even playing field, where mutual benefit is incentivized for both parties, in addition to offering a better opportunity to maintain the tenant-landlord relationship. Courts benefit, too, from reduced caseloads.

This program has worked well during the pandemic in Philadelphia, where the city’s Eviction Diversion program has mandated that landlords go to mediation with their tenants before they are able to evict them.

Philadelphia is unique, though, and many municipal and state jurisdictions face political opposition to any measures perceived to be biased toward renters or more costly than conventional courts. The program also fails to address informal evictions.

While not a cure-all, and while an eviction notice mandating mediation remains frightening for many, we believe this could be an important step toward empowering both landlords and tenants to achieve an agreeable, workable solution that cuts costs and effort for all involved.

Community-Based Housing Navigator Programs

Given the discouraging prevalence of isolation during the eviction process, the potential to empower tenants to find their best solution through support and companionship is very important to experience-centric innovation in the eviction landscape.

With housing navigator programs, like the NAACP pilot program in Richland County, South Carolina, tenants at any stage of the eviction process can be connected with a community member who has been trained to understand the local eviction landscape and can educate tenants on their options and the available resources. This engages the local community on the issue of eviction, and provides both support and a know-your-rights knowledge base for tenants.

Still, this comes with challenges: navigator recruitment and training, maintaining the boundary between advice and Unauthorized Practice of Law, and the organizational overhead. Even when those are addressed, if tenants in need don’t know about the program, it can also be yet another helpful resource that goes unused. Nonetheless, when executed correctly, navigator programs have the potential to guide isolated and uninformed tenants to their best interest outcomes.

Renter Education and Simplified Notices

Most importantly, in our conversations with tenants, we found that eviction is nearly always an emergency. Even when renters expect recourse for nonpayment of rent, or were threatened by their landlord in the past, an eviction is always a moment of stress that no one feels prepared for. The opportunity here is obvious: What if eviction were something that every renter was prepared for? Or, what if every tenant at least knew one website to visit or number to call in case of urgent eviction needs?

This is the case in Milwaukee, where the Rent For Success Program has worked hard to ensure that every tenant in the city has access to basic information and education to enable successful renting, beneficial to both tenants and landlords. While this solution may meet the most needs, and serves a clear function to better enable the earlier two, it too has challenges. How does one implement such a program? Is it mandatory for all municipal renters? Despite these questions, education is an exciting opportunity for individual municipalities to develop unique, local programs that can iterate, evolve, and grow to have tangible impacts on both landlords and tenants.

Courts should also follow best practices in transforming eviction lawsuit notices — like their Complaint and Summons. See the Legal Design Lab’s redesigned eviction complaint made in conjunction with Hamilton County Courts in Ohio.

Next Steps for Tenants & Eviction Prevention

From this initial class project, our Lab is working on a larger research project to understand the key barriers that tenants and landlords have when it comes to accessing the justice system & services that can help them avoid evictions — and get to stable, safe housing.

This includes:

- Our Legal Design Lab’s collaboration with the National League of Cities on the Landlord Engagement Lab, working with local governments across the US on engaging more mom-and-pop landlords in eviction prevention

- Promoting the Lab & NLC toolkit for courts, government and legal aid to improve their community outreach & eviction help services

- Research projects interviewing more tenants and landlords about their barriers to accessing justice and setting up stable, safe housing relationships

- Ongoing work in the Eviction Prevention Learning Lab city cohort to create new interventions that can prevent evictions, and then evaluate their impact

Please write if your group is also working on eviction prevention or similar challenges — and what you have learned about people’s barriers to getting help and resolving their problems in safe, equitable, and just ways. What can we be doing better in our courts, legal aid groups, and rental assistance efforts — to better engage, activate, and empower people with housing problems?