A report from the students in the Autumn 2023 Stanford Law/d.school class “AI for Legal Help”, 809E.

Please explore this January 2024 report from the Stanford policy lab/design lab class “AI for Legal Help.” The students interviewed adults in the US about their possible use of AI to address legal problems. The students’ analysis of the interview results cover the findings and themes that emerged, distinct types of users, needs that future solutions and policies should address, and possible directions to improve AI platforms for people’s legal problem-solving needs.

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Survey Design and Research Methodology

- User Research Findings

- User Research’s Implications for the Legal Help

- Future Ideas for the AI Platform

- Ideas for Future Research

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

The emergence of language models, like ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Bing Chat, has given individuals the ability to seek advice quickly with minimal upfront costs. However, there are challenges associated with these tools, such as the potential for misinformation, incomplete responses, and the need for user expertise. This report explores the utilization of Language Models (LLMs) for legal guidance through a novel set of user interviews and suggests areas for improvement.

This report accomplishes several things. First, it provides a primer on generative AI. Second, it describes the methodology of our interviews. Third, it reviews our research findings, focusing on users’ engagement with and trust in AI tools, differentiated by users’ prior exposure to AI tools. Fourth, it reflects on the implications of our survey results for the potential risks and benefits of AI use in the legal help space, as well as a synthesis of the user needs highlighted by our research. Finally, it offers several recommendations for the future use of AI for legal help: efforts to increase algorithmic literacy, improved warnings regarding legal advice, and broader improvements to user interfaces such as accessibility enhancements as well as verification icons. We conclude by identifying avenues for future research, including expanding the sample size and engaging in group interviews.

Introduction

New technologies have transformed the legal aid field, especially with the emergence of language models (LLMs) powered by advanced artificial intelligence (AI). This study explores the use of LLMs in serving as a tool to assist lay people with their legal questions. Specifically, our research focused on three key AI platforms: Open AI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and Microsoft’s Bing Chat.

Generative AI (“Gen AI”) chatbots have emerged as an alternative for everyday issues. Developers have built Gen AI chatbots on a machine learning model known as a large language model (LLM), which is trained on extensive amounts of information and can produce surprising results that mimic human language and interactions. This feature makes Gen AI chatbots well-suited for tasks like answering any human issue since they can access vast amounts of information and data and formulate tailor-made answers for their users. Gen AI chatbots can also provide information, respond to queries regarding the law, provide references for organizations, and even draft entire documents.

Is AI going to be good or bad for legal help online?

We hypothesize that using Gen AI chatbots for legal aid offers potential advantages to users. First, chatbots enable cost-effective access to information—an invaluable resource for individuals who cannot afford to hire an attorney or contact a legal aid organization. Second, Gen AI chatbots can potentially expand legal help to populations traditionally underserved by the system. For instance, they can guide in areas or cater to non-English speaking communities.

Even with these benefits, employing AI chatbots for legal aid comes with risks. One such risk is that these Gen AI chatbots may hallucinate and deliver incomplete responses, and their use “raises a host of regulatory and ethical issues, such as those relating to the unauthorized practice of law.” (See more from Andrew Perlman’s piece). As it can be analyzed, these are risks associated with people over-relying on AI chatbots for legal issues, mainly legal answers.

Some responses from our participants illustrate the divergent thoughts about the future of AI for legal help. When asked to describe AI and their experiences trying to use it for legal problem-solving, participants had very different descriptions:

How do participants understand generative AI?

“If it was a chip in my brain.” Q4.7; P43

“Publish the source more, I didn’t know about AI, promote AI.” Q4.8; P30

“It seems like it has feelings — I understand your situation.” Q4.2; P25

“A hydrogen bomb covered by cotton balls. AI, unfiltered as it is, is scary intelligent, but the version that is released to the public is so watered-down. So there is a huge discrepancy as to what people think and what it actually is. In reality, it is becoming dangerous — the public doesn’t know because it’s watered down so much.” Q2.8; P43

Our project’s goal is to get community input on how to make these tools accessible, useful, and safe. The main goal of our study is to examine how people interact with AI tools in the legal aid field. Specifically, we seek to understand user behaviors, levels of trust, and how their perceptions might change after interacting with Gen AI chatbots. By exploring user perceptions and their experiences with these systems, we can gain insights into their strengths, limitations, and areas of opportunity.

Short Background on Generative AI

ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Bing Chat are applications built on a Generative AI model known as a Large Language Model (LLM). With recent innovations in transformer model technology, such as the mathematical attention described in the hallmark paper “Attention is All You Need,” the modern LLM is extremely powerful, allowing AI chatbots to communicate at a level similar to humans. For this reason, everyday people are increasingly turning to AI chatbots to help solve their problems; and with that, comes seeking legal advice.

Academic literature attempting to evaluate the accuracy of LLMs applied to legal reasoning tasks is rapidly developing. While there have been headlines about GPT-4 passing the Uniform Bar Exam, much is still unknown about how often LLMs “hallucinate” or provide wrong information in legal contexts. Legal benchmarking datasets like LegalBench (Guha, et al.) come closer to analyzing the efficacy of legal advice from chatbots, as they attempt to gauge legal reasoning skill among LLMs. The future of AI for legal help depends on continued academic efforts to evaluate and improve the accuracy of LLMs in the legal context; our research at present, however, considers how helpful AI chatbots are at helping people address legal issues.

One attempt to capture this need is the self-proclaimed “world’s first robot lawyer”, DoNotPay, a subscription-based AI chatbot service that attempts to expand access to legal advice; however, they’ve been the subject of a series of lawsuits regarding the unauthorized practice of law which has significantly hampered their services. That hasn’t stopped attorneys from using AI chatbots, most notably with a New York attorney filing court documents using hallucinated information from ChatGPT. Given these issues, our research also considered the potential harms from AI chatbots in addition to the potential benefits for access to justice.

Survey Design and Research Methodology

We conducted and reviewed a total of 43 interviews for this project. About half of interviews were conducted over Zoom and the other half was conducted in-person at the Santa Clara County Family Courthouse. The Zoom interview participants were selected through a Qualtrics recruitment service that ensured that the respondents had some familiarity with landlord or tenant issues (i.e., have been a landlord or a tenant); whereas the Courthouse interview participants were recruited randomly in-person at the courthouse lobby and spanned a variety of needs, from those that were seeking their own legal assistance to those accompanying friends and family.

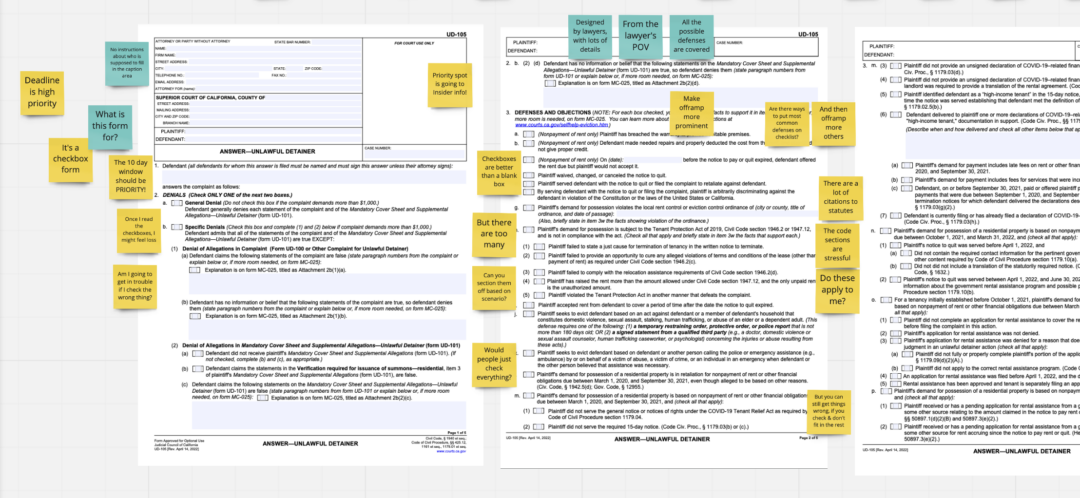

Each interview consisted of the following format. A team of around 2-3 researchers met with one respondent and asked questions from a secure Qualtrics form. Most questions required respondents to reply via a sliding scale (0 to 6) to capture the wide array of potential responses. The interview consisted of three parts: (1) background questions about the respondent and their experience with legal issues and the internet; (2) a guided interaction with an AI chatbot (e.g., ChatGPT, Google Bard, or Bing Chat) to resolve a fictional issue; and (3) reflections on the tool and demographic information. Before proceeding, we informed the participants to not share any private/personal information when using the AI tool and that they were free to stop the interview at any point if they felt uncomfortable (with no penalty to their interview compensation).

In the first part of the interview, we asked respondents a number of questions about their experience in resolving legal issues and utilizing AI tools. We also asked the respondent to reflect on an issue with a landlord or a lending institution to get them in the mindset of how they might think about resolving these types of issues.

“How confident are you that if you had a legal issue, you would be able to resolve it?” (Q #)

“How often do you use the Internet to get answers to a problem you’re dealing with?”

“Have you ever used an AI tool like ChatGPT before?”

In the second part of the interview, we introduced respondents to a fictional scenario in which they arrived home to their apartment to find an eviction notice. We then gave respondents the option to choose any of the following AI tools: ChatGPT, Microsoft Bing, or Google Bard. On Zoom, respondents shared their screen as they interacted with the tool, and in court, respondents either directly interacted with the tool if they felt comfortable or conveyed their prompts to interviewers. If a respondent did not feel comfortable creating an account for a tool, as is necessary for Google Bard or ChatGPT, we directed them to Bing or offered to let them use the tool signed into a student account. We then observed and noted the participant’s reactions (i.e., how many prompts entered) to these prompts.

One important thing to note is that respondents were instructed to only enter details pertaining to the fictional scenario into the AI tool. A few courthouse participants began to enter information more specific to their situation into the tool, but we re-directed users from entering this information and asked them to input information only from the fictional situation. As such, we do not believe any users entered any private information into the tools. This is important to note as the privacy policies with various AI tools are either undesirable or unclear; for example, ChatGPT explicitly logs all conversations and uses it as training data.

In the third/final portion of the interview, we asked users about their experience with the tool as well as any suggestions for improvement and collected information on their demographics. In total, the interview took approximately 30-45 minutes. At the end, we compensated all interview participants with a $40 Amazon gift card for the interview and gave them contact information if they had any additional follow-up questions.

User Research Findings

User Typology: Beginner, Intermediate, and Experts

Three User Types Based on AI Familiarity

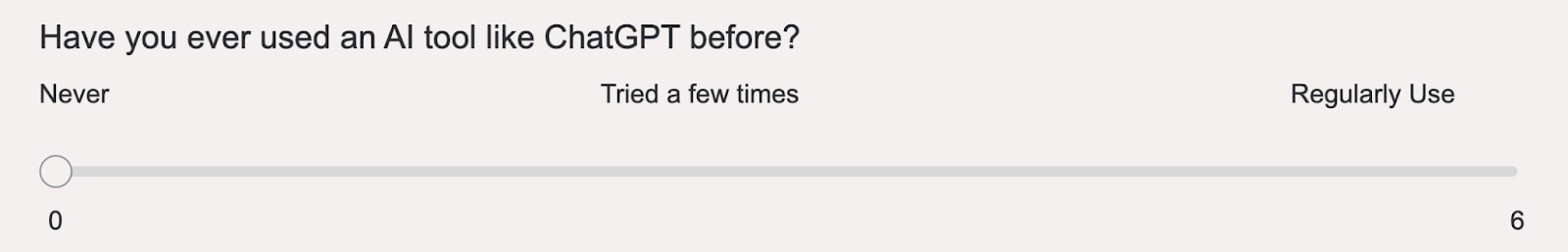

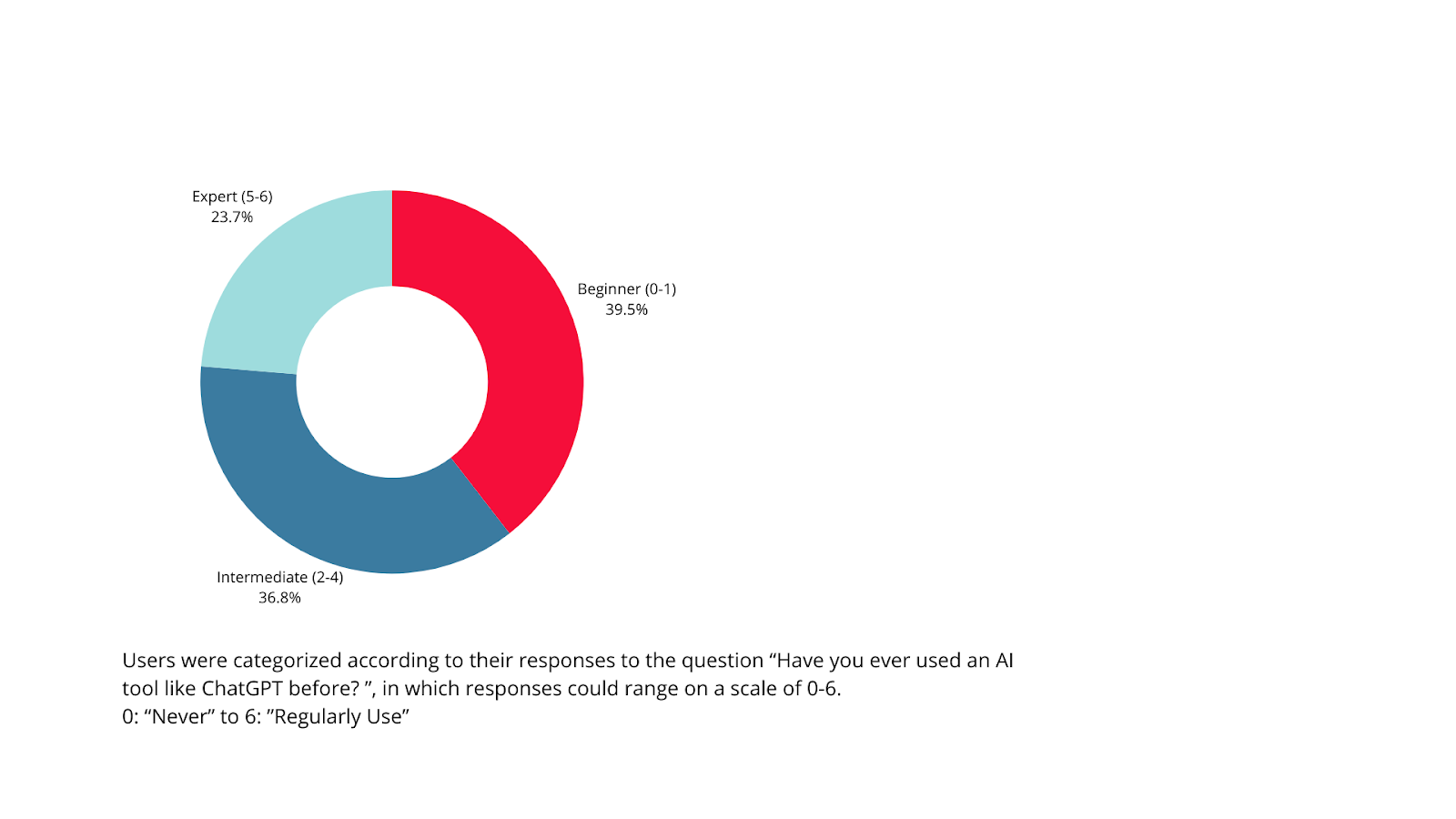

To facilitate our analysis, we grouped users into three different types with disparate behavioral patterns but similar preferences and needs. We determined these three broad categories based on respondents’ self-reported familiarity and experience with AI. Specifically, we asked respondents “Have you ever used an AI tool like ChatGPT before?” Users answered the question on a scale of 0 to 6, with 0 representing “Never” and 6 representing that the respondent “regularly uses” AI tools.

We established three groups: Beginner (response of 0 or 1); Intermediate (response of 2, 3, or 4); and Expert (response of 5 or 6). Beginners constituted roughly 40% of respondents, intermediates constituted about 37%, and experts constituted about 24%.

Users were categorized according to their responses to the question, “Have you ever used an AI tool like ChatGPT before?” To which they responded on a scale of “Never” (0) to “Regularly Use” (6).

The beginner user type is someone with little to no experience with AI. When asked how they would describe AI to a friend or how they would compare it to something else (Q2.8), they responded that they would not know how to explain and have not even interacted with the tool.

“I couldn’t explain it. I don’t know what it is.” (P30)

“I don’t know. I never used it.” (P39)

The intermediate user type captured those that had previously used AI but were not familiar with all the features. A large portion of respondents used Google search as an analogy (Q2.8).

“It’s an advanced form of using a Google search that you can ask more specific questions and receive specific answers.” (P12)

“A very smart chatbot that also searches the Internet. It’s kind of like customer service, but online.” (P23)

Finally, the expert user types were self-reported regular and confident users of AI–those who know the functions and can interact easily with the tool. When asked how they would define it, they provide more complex and creative answers (Q2.8) that denote a deeper understanding of how the algorithm works. We observed that the more knowledge the participants had, the more accurate, creative and diverse the answers they gave.

“[It’s an] open-ended learning platform.” (P17)“It’s like a go-to kiosk. If you don’t have an immediate family member to speak to, then you turn to the Internet.” (P43)

“It’s a very advanced but imperfect predictive text mechanism. It essentially takes data from the Internet, users, all manners of sources and tries to arrange that data into logical output. It doesn’t actually think in any way. It really strives to please and [give] answers to the question. It’s not always a good thing. But it tries.” (P8)

Attributes of the 3 User Types

Confidence Levels

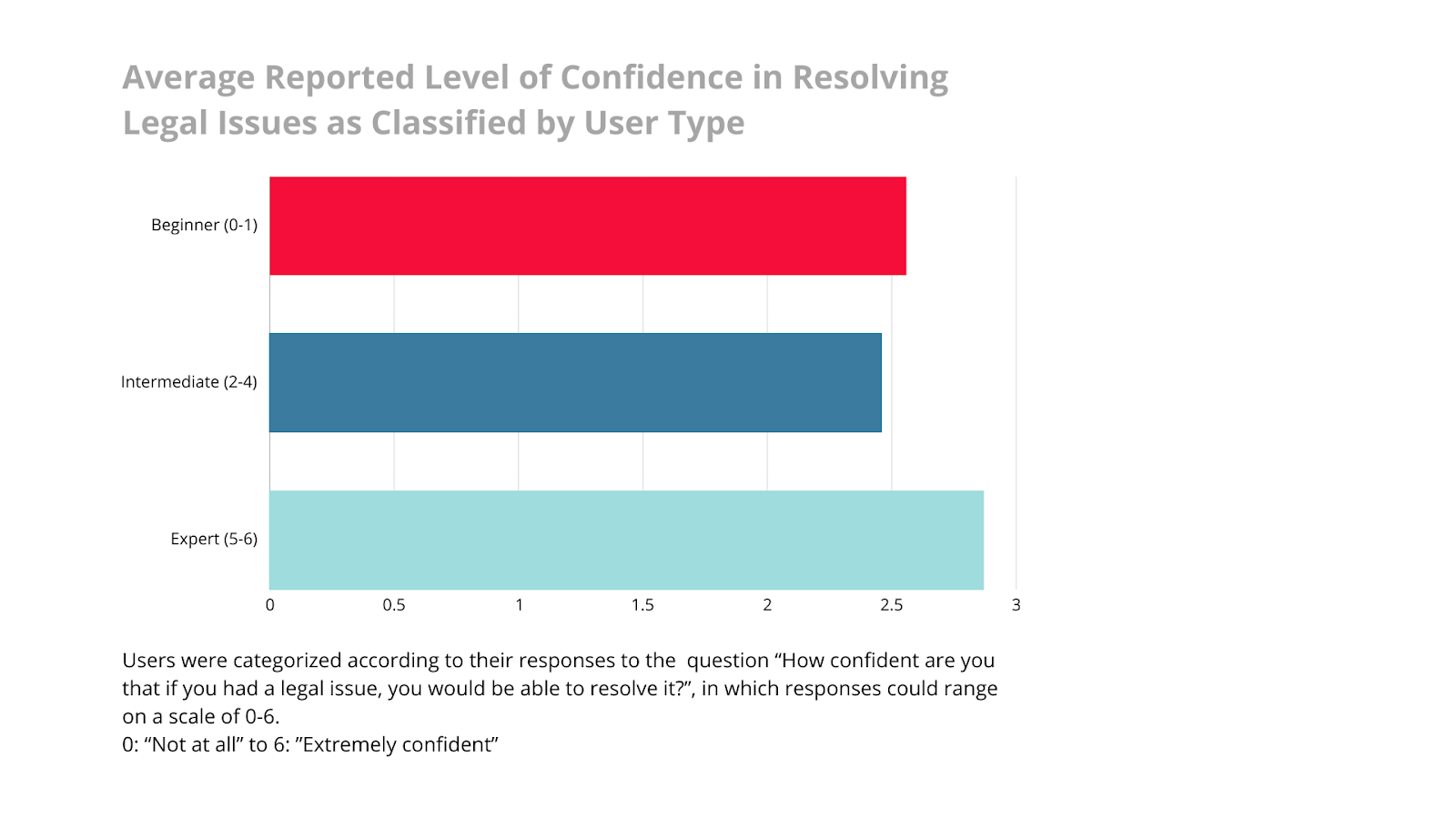

Understandably, the expert users self-reported more confidence in resolving legal issues on their own compared to beginners and intermediates, as shown by the chart below.

Participants Recruited Online vs. In-Person

There were noticeable differences in participants who we had recruited online & interviewed over Zoom and those we had intercepted in the courthouse lobby & interviewed in person. Zoom respondents were more likely to be intermediate and expert AI-tool users and court respondents were more likely to belong to the beginner group. This difference is likely due to the method of participant selection. Zoom participants were recruited by Qualtrics Research Services, an online survey platform, and likely were more tech-savvy to begin with.

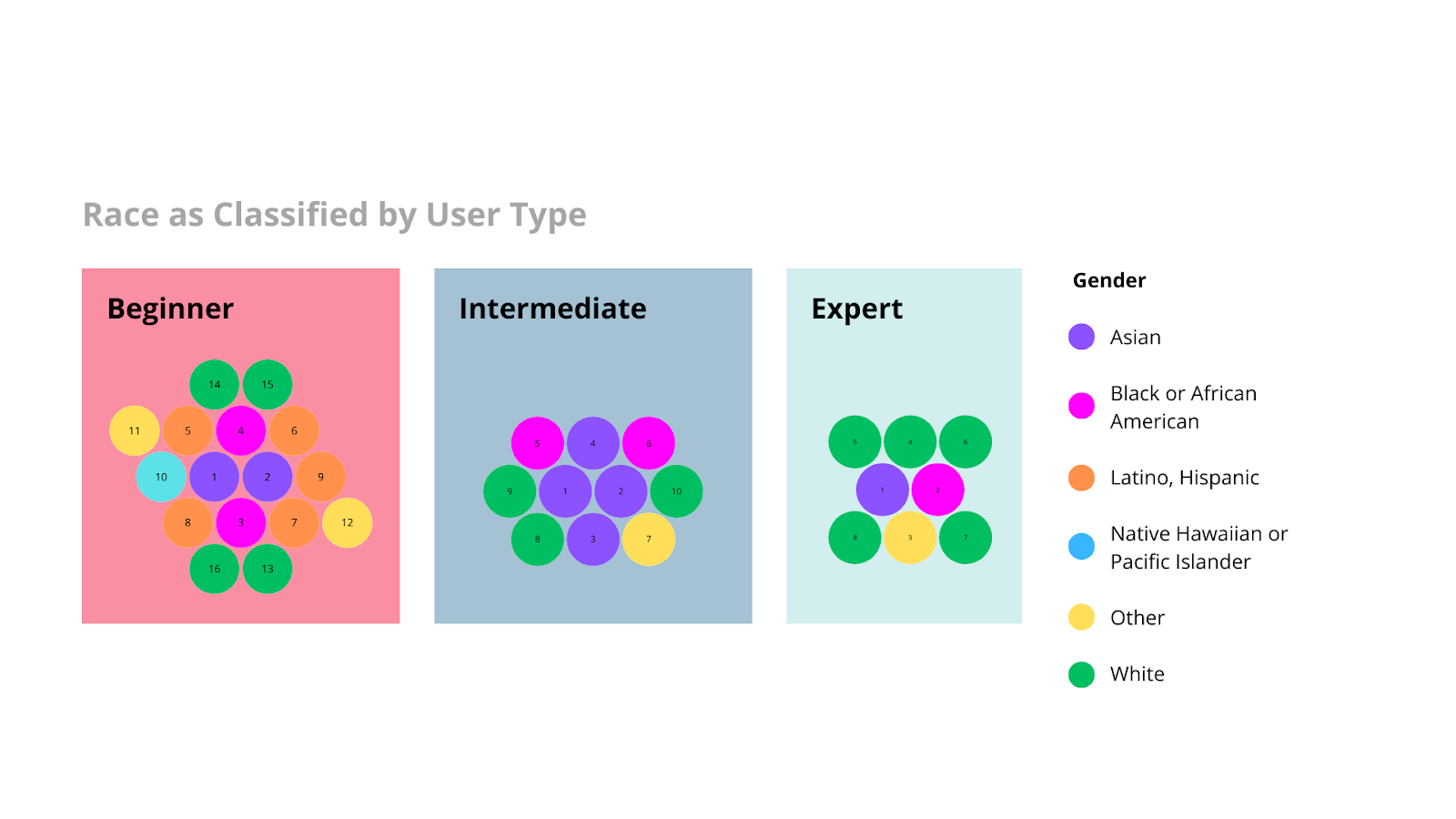

Demographics

We also observed demographic differences across our three user groups. Experts were generally more likely to be White, whereas our beginner users were more racially diverse. Despite our limited sample size, this accords with research that shows that race and socioeconomic status often impose barriers to accessing technology.

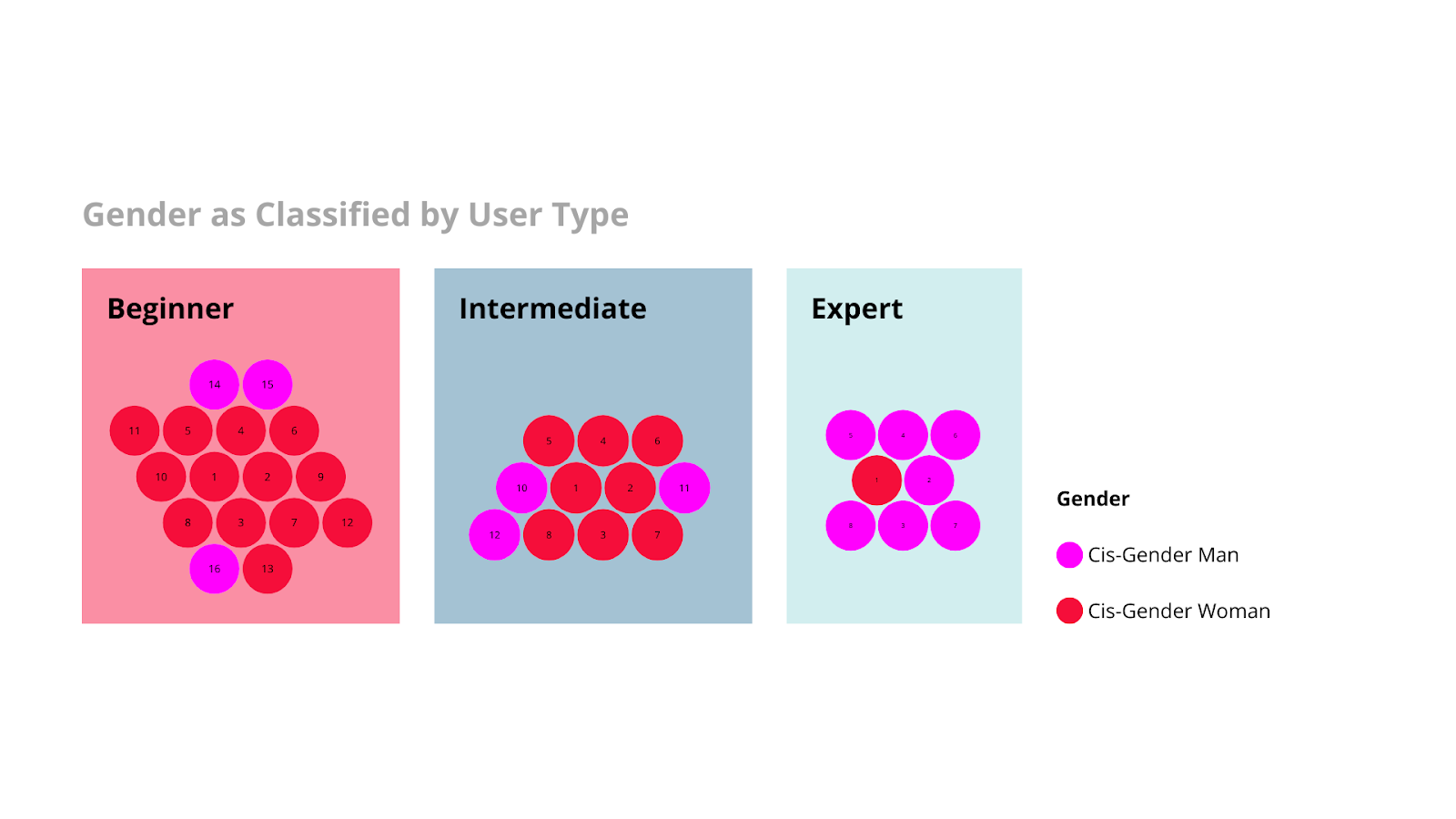

Experts were also more likely to be men, whereas women were more likely to be beginners.

We did not observe any clear correlation between age with the knowledge one has about AI. However, there might be correlations that we were not able to observe due to our limited sample.

Behavior Patterns of Different Users

Throughout our interviews, we noted differences across our user types at four key steps on the user journey:

(1) the prompts users entered into the AI tool;

(2) users’ reaction to the usefulness of the information provided;

(3) users’ level of trust in the tool before and after using it; and

(4) what users reported they would be most likely to take as next steps after their AI interaction.

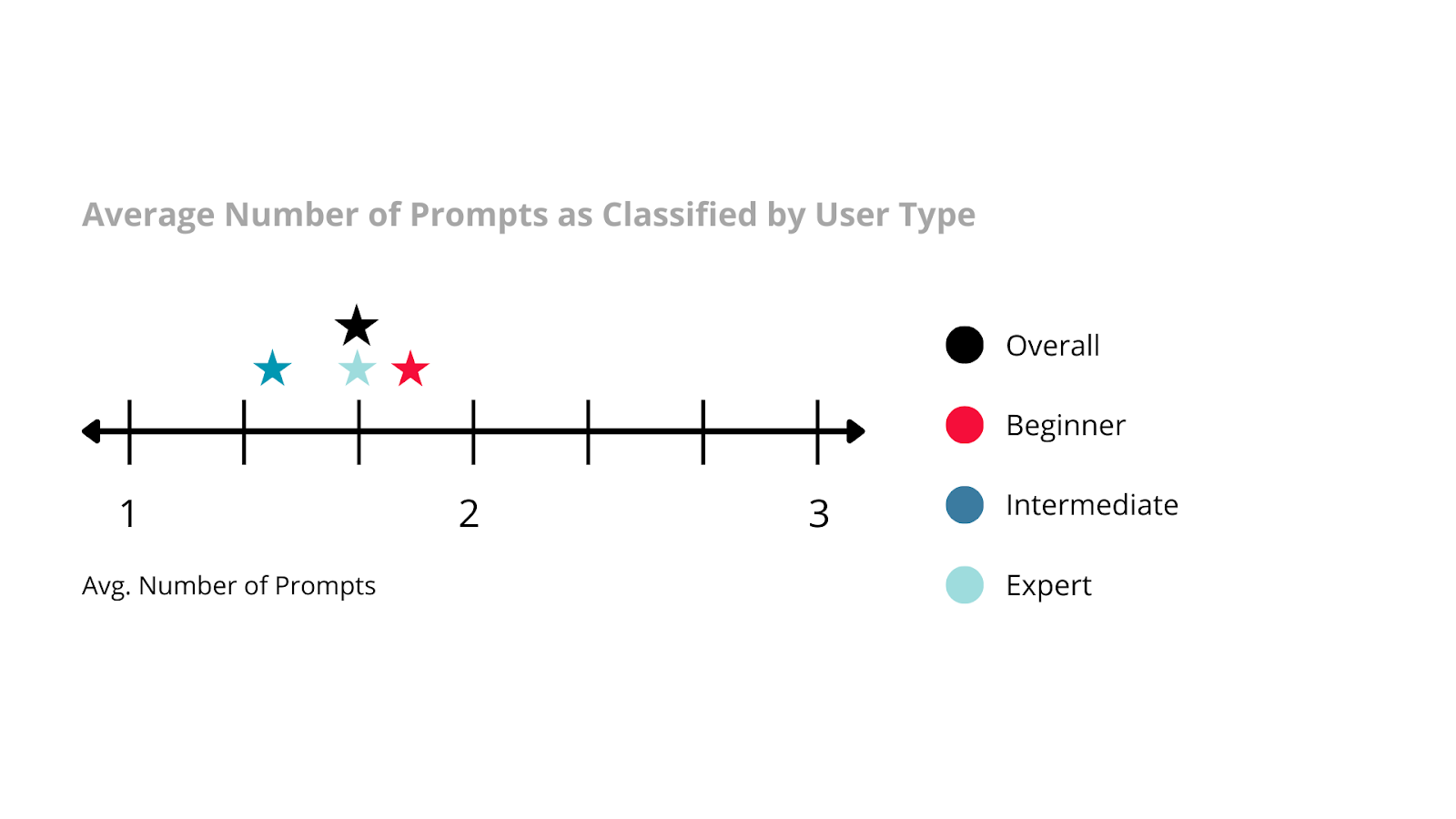

Prompts Entered

Across our user types, the average number of prompts entered was 1.6. Beginners asked the most number of prompts, averaging around 1.8.

An interesting observation emerged when we looked at what each user types entered. Beginners entered very broad prompts, followed by intermediates. Finally, experts tend to enter specific requests. For example, a beginner user entered “renters rights” in response to the hypothetical eviction situation that we gave (P30). An intermediate user narrowed down by location, “What are my rights in the state of Florida for eviction?” (P20). Lastly, an expert user asked the chatbot to “please list websites that might be helpful” (P17). More specific prompts enabled generative chatbots to give more relevant and useful information. Thus, this correlates to the slightly more positive experience reported by experts.

Satisfaction with the AI Tool

Experts were generally more satisfied using the chatbot than other user type groups. When asked “How was that experience for you?” experts expressed the highest level of satisfaction out of the user types at 4.7 out of 6 on average, where 6 represented “extremely helpful” and 0 represented “not helpful.” This was followed by beginners at 4.3. Finally, our intermediates reported the lowest average satisfaction score of 3.7. Respondents across user types preferred generative chatbots over Google, reporting that the chatbots offered more relevant information in a condensed format.

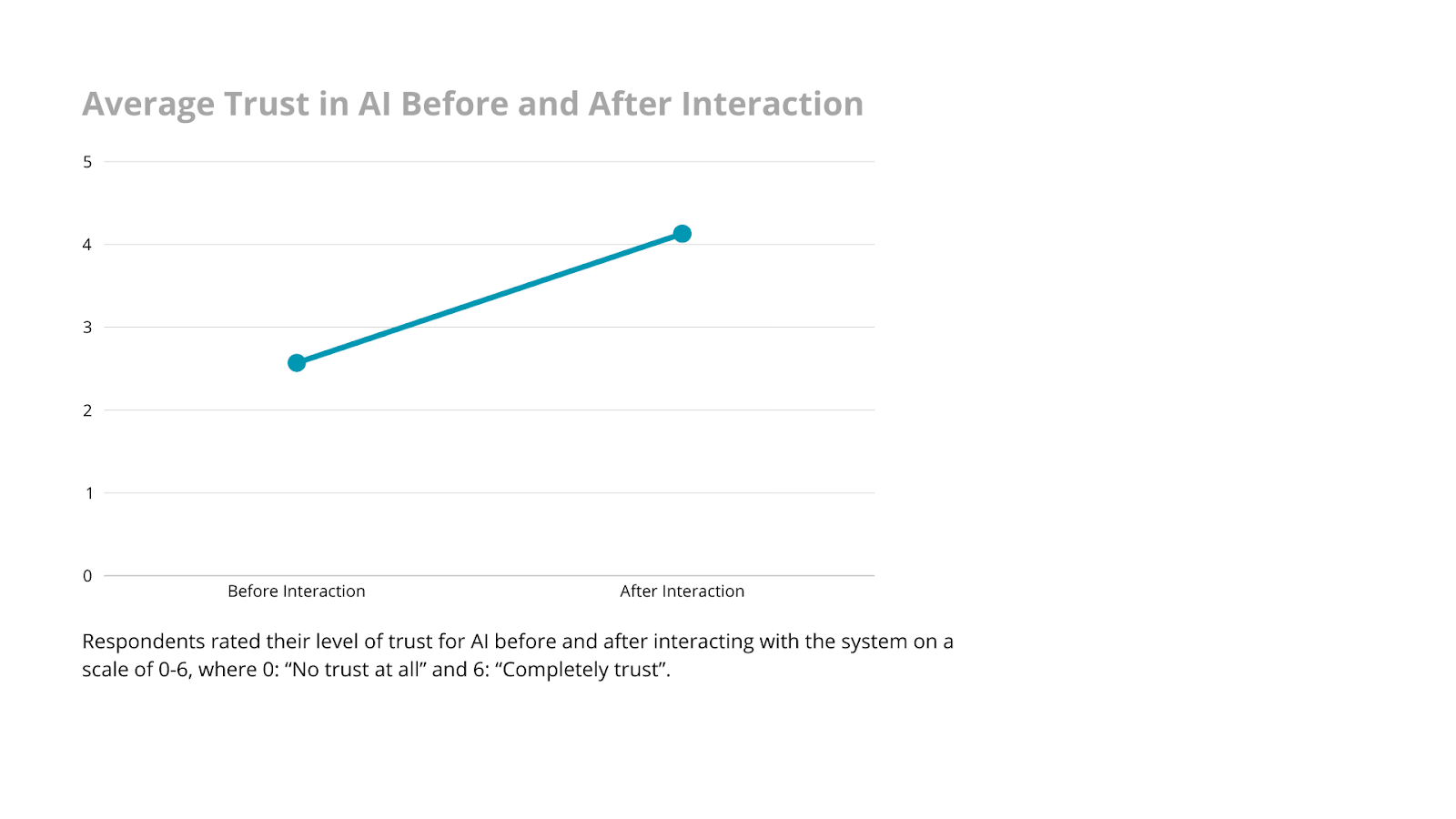

Trust in AI for Legal Problem-solving

Before and after using the AI tool, respondents rated their level of trust in the tool on a scale of 0-6 where 0 indicates “No trust at all” and 6 indicates “Completely trust.” Before using the tool, users on average distrusted the AI tool more than they trusted it–the average score was a 2.3 out of 6. After using the tool, however, respondents demonstrated an increased level of trust–the average score was a 3.4 out of 6.

Within that increased level of trust on average, there was still variety in user experience. For example, when an “expert” user was asked to explain their high trust score, they reported that the tool “gave [them] factual information and websites that [they are] familiar with” (P9). However, a “beginner” user reported that they still felt low trust after using the tool because they “cannot confirm that the information is accurate and credible” (P7).

Another pattern we observed was that there was often a gap between the trust that we observed in users in practice and the trust they reported upon prompting. For example, a handful of people who remarked that they did not trust the tool when asked made positive comments when reading the results from the tool, often seeming to take specific facts (such as the number of days required by an ordinance) for granted.

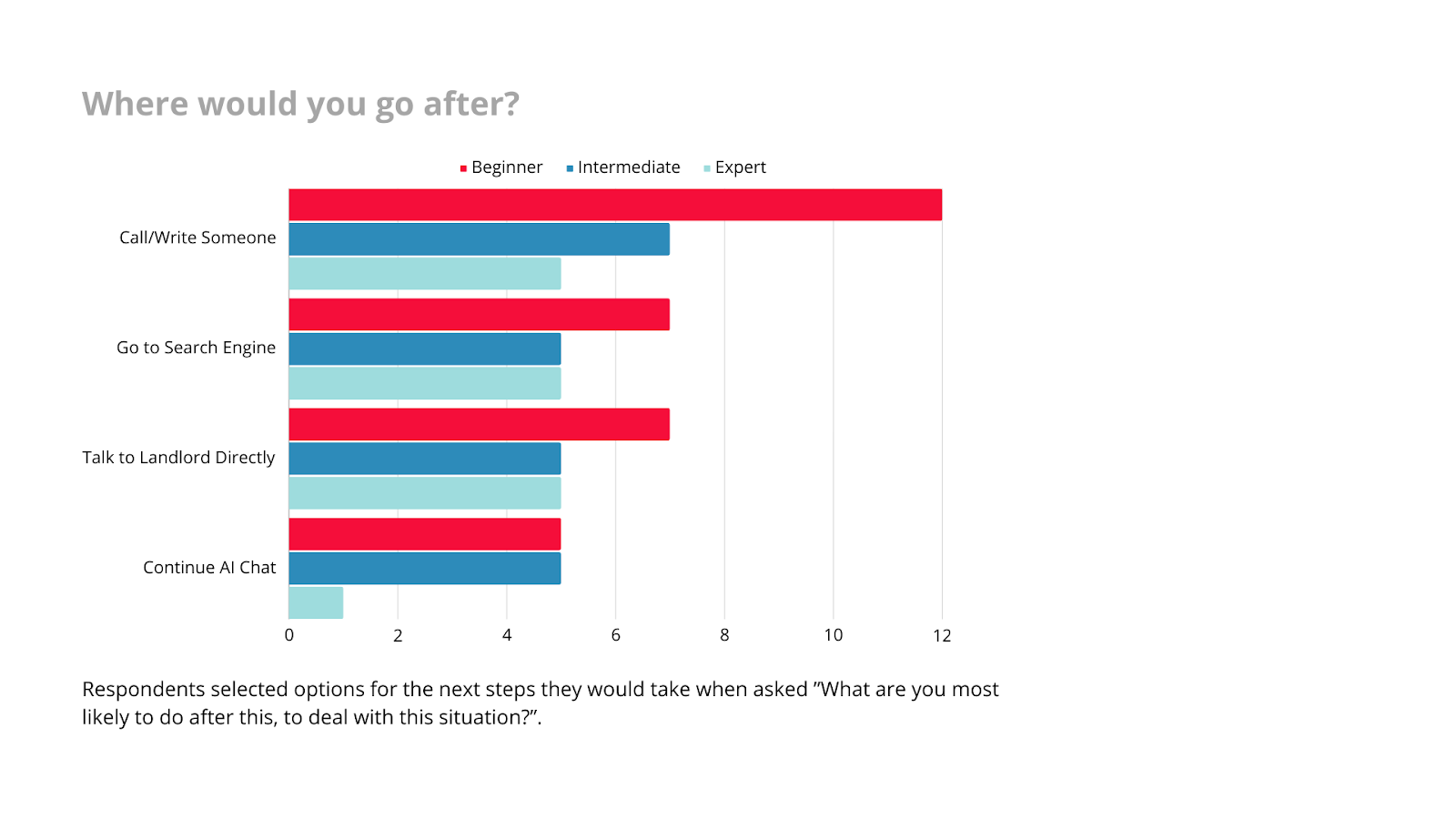

User’s Next Steps

Finally, after interacting with the AI tool, we asked respondents how they would continue to resolve their fictional scenario. The options were:

(i) call or write someone,

(ii) go to a search engine,

(iii) talk to their landlord directly, or

(iv) continue chatting with the AI tool.

Respondents could select multiple options.

All respondents were most likely to call or write to someone to continue resolving their issue. Notably, for all user types other than intermediate, continuing the AI chat was the least selected option. This could be because users did not find the tool helpful, or it could be because users got everything they needed from their interaction and thus would not need to interact with the tool further.

User Research’s Implications for the Legal Help

Observed Benefits, Mistakes, and Risks

Benefits AI can offer people seeking legal help

One major benefit we observed is accessibility. When compared to the alternatives of congested courts, inundation of free, untailored legal resources, and expensive lawyers, these platforms excel in availability. First, they provide immediate access 24/7 and at all locations. As one respondent noted, it’s like “having a personal assistant that you can utilize for personal and business use.” (P9) Second, they are generally available for zero to no cost. Although one needs internet access and may need to pay fees to use AIs in the future, AIs are still less costly than private lawyers. As one of our interviewees remarked,

“It’s very quick and easy to ask questions, get suggestions, and a detailed answer [from the tool]].” (P10)

Another major benefit we observed is understandability. The legal industry is notorious for being inaccessible and opaque – full of confusing statutes, procedural requirements, and “legalese” or legal jargon. Gen AIs, however, provide a user-friendly experience that helps non-experts digest and navigate legal issues. Gen AIs are very conversational: they often respond to questions in a dialogue tone and use language. As one interviewee noted, “It’s like using Google but [having] a conversation with you.” (P4) AIs are also direct: confronting a legal question, they tend to provide a summary followed by concrete suggestions for the user. Such benefits are quite noticeably important in high-stress situations where emotions may be heightened, and users can become quickly overwhelmed. In combination, these benefits create a tidy conversation through which users can understand the contours of their legal issues and walk away with actionable next steps.

Last, though largely unexplored in this report, there is a huge benefit in using the Gen AI’s translation abilities in assisting non-native English speakers. We conducted three interviews in Spanish and one in Mandarin Chinese. Bing Chat was notable in its ability to respond to non-English queries in our interview. The potential for non-English speakers to use these AI tools for their legal problems (i.e., drafting letters or answering procedural questions) is still in its infancy, but is worth mentioning Other users have also found emotional support from AIs as their conversational tone and directness help alleviate feelings of lostness and overwhelm.

Mistakes and Risks involved with AI for legal help

These tools, however, cannot substitute professional legal assistance as of yet. During our interviews, we observed two main types of mistakes in these Language Learning Models.

First, AI tools sometimes provide inaccurate information. One form of inaccurate information is hallucination. Specifically, AI tools sometimes provide fictional legal entities, resources, and cases. Another form is misrepresentation. In conversation, AI tools occasionally assume the racial, gender, or other demographic identities of their users. Consequently, AI tools would provide information that is both mistaken and insensitive, or offensive to the user.

Second, AI tools often provide incomplete information. In the legal context, AI tools are often tasked with listing specific rights, available resources, and actionable steps. In these scenarios, AI tools often fail to provide a comprehensive list without saying so. Staring at such a list, inexperienced users could falsely believe that “Nothing was missing, that was everything I needed.” In reality, given the complexities of legal issues, AI tools can rarely deliver exhaustive information.

Given these mistakes, researchers, developers, and policymakers should remain cautious of two salient risks. One, AI tools can induce overreliance. For non-expert users, AI tools’ answers to legal questions can not only seem complete, but also authoritative. Many interviewees gave AI tools a degree of blind trust, remarking that AI tools “sounded legit” or that “it’s hard for AI to do wrong.” Some even inferred that AI tools are particularly trustworthy in the legal realm. Consequently, users may forget to double-check the information provided or ignore warning labels to seek out professional advice.

Another risk is that unsophisticated users can fail to take full advantage of AI tools. As Language Learning Models, the level of specificity of Gen AI tools’ answers depends on how detailed the inputs are. Most of our interviewees, however, did not volunteer details and asked generic questions instead. Some of them had legitimate concerns about data privacy, but the lack of details in their questions has resulted in general answers that exacerbated the aforementioned mistakes.

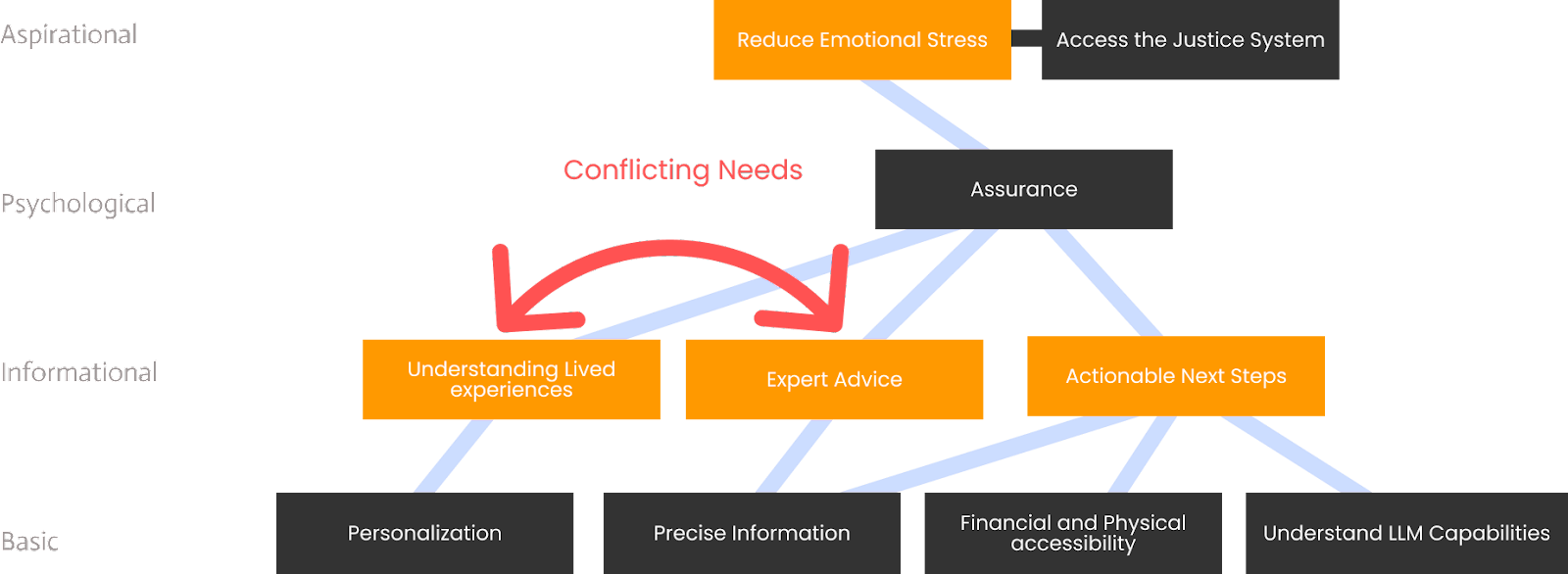

User Needs Hierarchy for Legal Help Tools

The user research findings point to general insights about what people need from a legal help tool — as well as specific insights about what they need from an AI-provided legal help tool.

Participants highlighted a desire to alleviate the stress associated with accessing legal assistance. Their struggle is further complicated by various factors impacting accessibility. The pressing issue lies in bridging the justice gap when individuals’ cases cannot be taken by legal aid groups.

Participants emphasized the necessity for enhancing the tool’s accessibility, both in terms of finances and physical usability. A Chinese-speaking participant expressed concern about potential language barriers impacting their access to aid through the tools. They expressed doubts about the accuracy of translated information, as articulated by one participant’s concern:

“My English is not very good, and we have language barriers understanding our options… My husband often says that he thinks the translated version of the information we get is not quite right” (P40).

Moreover, physical accessibility concerns were raised, exemplified by a participant’s request for larger font sizes to enhance readability: “I want to make the font bigger” (P26). This participant’s feedback sheds light on the need for improved physical accessibility within the tool to cater to diverse user preferences and potential physical impairments.

Participants also expressed significant concerns regarding the privacy of their data when seeking assistance:

“I don’t know where to begin, and I don’t want to guess because it’s logging personal information about me – I don’t want to put more personal information to get the answer I want” (P2).

A common thread emerged among participants, voicing a shared desire for clear “next steps” to resolve their legal issues. Their need for actionable guidance reflects a need for more precise answers, as articulated by one participant:

“I cannot confirm that the information is accurate and credible” (P7)

Underscoring the necessity for more definitive and trustworthy responses. The challenge arises when tools like ChatGPT provide generic information that might not directly address their legal challenges.

Participants sought a balance between receiving guidance from qualified professionals and leveraging the collective wisdom of crowdsourced knowledge like Quora or Reddit to navigate the justice system:

“Quora came up first, without even having to go to the site, seeing people’s questions like mine… I like Q&As, real human answers, and seeing other people having the same problem in detail as me — their emotions, what happened, and detailed answer not so general” (P6)

This tension between desiring expert guidance and accessing a pool of diverse knowledge sources underscores a pivotal conflict that any solution should aim to reconcile. Addressing this duality is crucial in crafting a solution that caters to these divergent yet interconnected needs of the users.

Based on the interviews we hypothesize that there is an overarching need to reduce the stress around accessing justice systems and providing assurance that they are following the right course of action to solve their legal challenges. This is aptly summarized by a participant who said:

“Because the main thing that I would want in that situation is confirmation. …. It’s good to get a second opinion, even if it’s from a soon-to-be-evil robot.” (P8)

This also underscores the trepidation that participants expressed about the AI tool like ChatGPT. They think that these tools for now seem to be helpful but soon might become inaccessible and might use their data in counterproductive ways.

To visually represent these diverse needs among participants, we crafted a Needs Hierarchy Chart. This chart aids in identifying and prioritizing user needs, ensuring that the solutions developed align effectively. The chart encompasses various levels of needs, from fundamental necessities at the chart’s base to more intricate or aspirational needs at the top

Level 1 revolves around Basic needs like personalization, precise information, and accessibility. These needs cover both financial and physical aspects and are crucial for individuals seeking assistance or support.

Progressing up the hierarchy, Level 2 addresses Informational needs. At this stage, there’s a complexity arising from conflicting needs. While troubleshooting their legal woes people might concurrently seek guidance from experts while valuing insights gained from shared experiences of average individuals on platforms like Quora or Reddit.

There is a need to use this information to understand and execute the actionable next steps. It underscores the importance of having a clear plan or strategy to address identified issues, bridging the gap between understanding information and implementing it.

Levels 3 and 4 encompass psychological needs and aspirational needs, covering emotional stress reduction, and seeking reassurance. These needs emphasize the importance of crafting solutions that are not just functional but also sensitive to the emotional state of the users. This involves designing interfaces, processes, and support systems that are intuitive, comforting, and capable of reducing any additional stressors a user might encounter.

Future Ideas for the AI Platform

AI cannot replace lawyers, but with the right changes, it can help people get started on the right path with their legal questions. People already employ AI tools with a high level of trust, so completely halting their use may not be possible. However, various stakeholders (legal aid groups, government organizations and technology companies) should understand the changes below to redefine AI as a tool for access to justice. We believe that with the right changes, the benefits that AI poses can be retained while minimizing the risks it poses. We hope the below proposals can mitigate some of the risks that come with using AI while maintaining its benefits.

Idea 1: Increasing Algorithmic Literacy

During our interviews, we noticed that user trust in AI chatbots fluctuated between pessimism and optimism. This oscillation between pessimism and optimism leads to suboptimal outcomes, which can hinder people from harnessing AI chatbots to seek legal help. It is necessary to foster a pragmatic view of AI chatbots to maximize their ability to build user trust and serve as a reliable tool to increase access to justice.

The existing deficit in user trust can be bridged by building algorithmic literacy and awareness about AI. Over the past decade, we have witnessed a global push towards digital literacy. Digital literacy builds off of general literacy and allows people to use digital technologies to find, assess, generate and exchange information. Typical digital awareness efforts attempt to enable the user to navigate the internet, have a basic understanding of how to use devices, how technology works, critical thinking, an assessment of information online and an understanding of risks associated with sharing information online. These skills are essential in an increasingly digital world.

However, current digital literacy programs seldom include targeted attempts to increase “algorithmic literacy”. Algorithms underpin online interactions among users on platforms. The users’ demand for ‘relevant’ content has led platforms to deploy powerful recommender systems that create algorithmic filter bubbles and echo chambers. As a result, users are confronted with algorithmic bias and the rapid spread of misinformation across information systems online. Over the past decade, we have witnessed how algorithmic bias and misinformation have led to polarization, increased intolerance and distrust and proliferated hate and violence across societies. Therefore, it is imperative to view algorithmic literacy as a critical subset of digital literacy programs.

At the outset, algorithmic literacy workshops should focus on building awareness among people from diverse demographic groups that information systems have dramatically changed over the

last decade online. To this end, workshops should focus on helping people understand the following:

- Algorithms rely on data. Platforms online collect, track and process data about every aspect of our daily lives; the people and locations we visit, the content that we consume online and the news that is likely to capture our attention. These data points are typically aggregated with other information from our smart household gadgets, virtual assistants and data brokers.

- The algorithmic profiling of users based on aggregated datasets enable platforms to process data in real time. The data is used to determine and predict various aspects of the users’ social lives. For instance, such datasets could determine who could get a job, who is likely to have a better credit score and less likely to default on payments and access to education and employment opportunities. lesser risk of default and access to education and employment opportunities.

- AI chatbots (and AI systems at large) are trained on such datasets, which means that existing societal biases can be perpetuated and amplified by algorithms. For instance, AI systems could recommend a prison sentence based on data aggregated from criminal justice systems that have a history of racial discrimination.

- News published by traditional media outlets is redistributed to users based on recommender systems and other powerful algorithms deployed by platforms. This leads to a disaggregation of information. As a result, users often lack context when they consume news or any information online.

- The growing distrust in mainstream media, pressure from large conglomerates and advertisers and the lack of editorial freedom has contributed to the rise of alternative media sources. Alternative media seldom lacks the resources (or the motivation) to fact-check information before disseminating it online. As a result, the lack of verified information has contributed to the destabilization of information systems online.

The technical infrastructure and policy decisions that underpin the inner workings of algorithms online and our information ecosystems are opaque by design. The public lacks awareness about the opacity and power dynamics at play across information ecosystems online and how that power is wielded.

Building algorithmic literacy among people from diverse demographic groups requires developing material that fosters inclusivity, empathy and specific solutions.

How can we use design thinking to increase the workshops’ efficacy?

Project Information Literacy (‘PIL’) is a non-profit research institute that researches to study how young adults interact with information resources for school, life, and work and to engage with the news. PIL has conceptualized the following visual to capture the current state of play.

Potential outcomes of algorithmic literacy workshops

Successful algorithmic literacy programs can aim to develop the following skills in participants:

- Learning to be critical of information and content that users access and consume online,

- Knowing how to use AI chatbots effectively by learning to input prompts that the AI chatbot is likely to engage with in a meaningful manner,

- Believing that AI chatbots cannot replace professional legal advice from legal aid groups and lawyers,

- Verifying responses generated by AI chatbots with other sources,

- Building awareness about the risk posed by AI chatbots i.e. the possibility of generating inaccurate information, bias, hallucinations and alignment issues,

- The willingness and ability to engage in the global push to regulate AI.

Idea 2: Better Warnings for Safe & Informed AI Usage

Our user research indicated that many people using AI tools do not know how to use it safely. It also indicated that not everyone will engage or be affected by traditional warnings about how to strategically use (or not use) the information the tool provides.

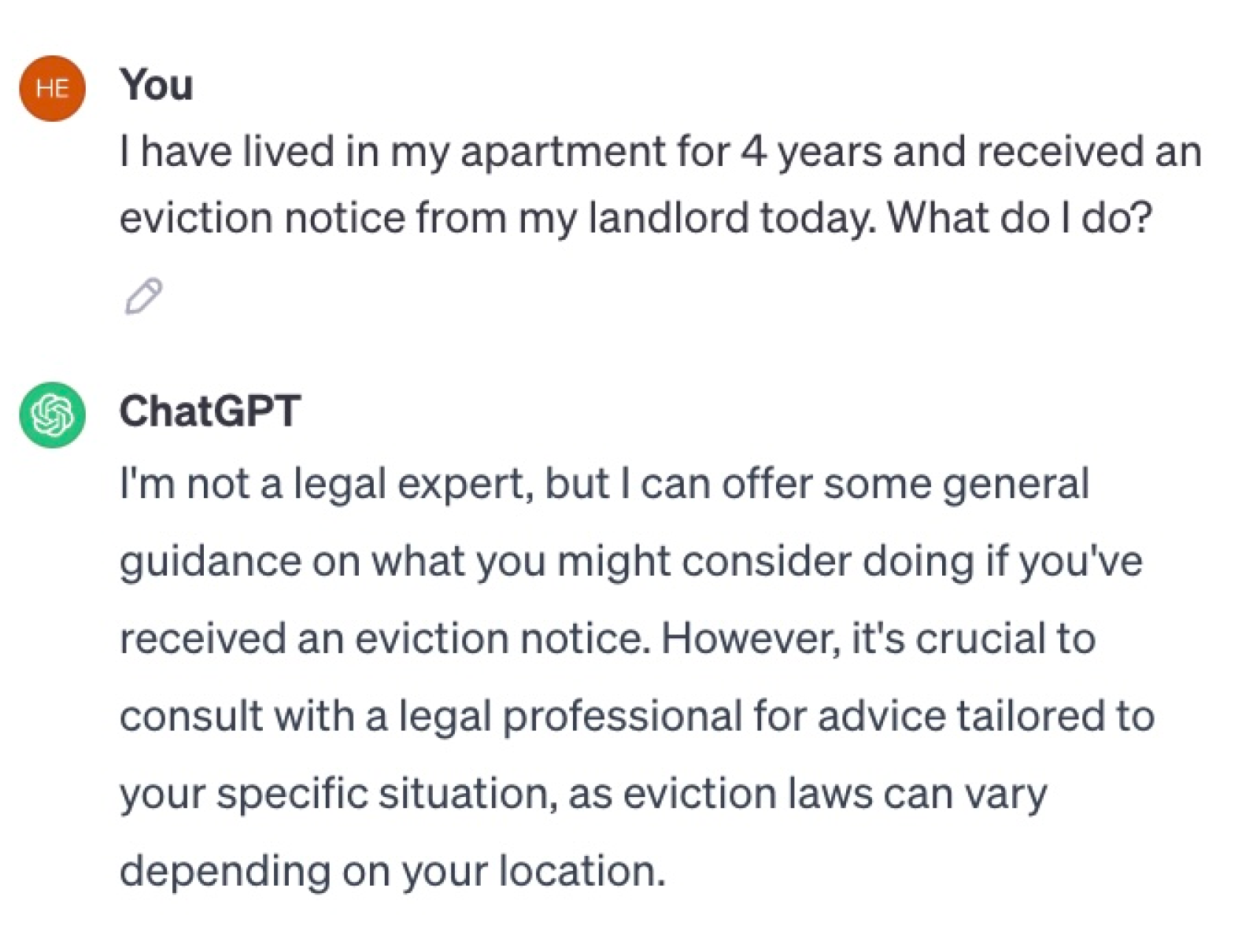

AI developers could create better warnings for when to consult an attorney. These warnings are changing as AI tools develop, as evidenced by the varying disclaimers we saw throughout our work. When we started our work in September 2023, Bard, Bing, and ChatGPT generally used some form of a disclaimer that directed the user to consult a legal aid organization or attorney in its response. ChatGPT’s disclaimer is pictured below.

In December 2023, ChatGPT started including another disclaimer below the chat box that warned users of the tool’s potential for mistakes, pictured below.

Bard’s AI tool now includes a similar disclaimer.

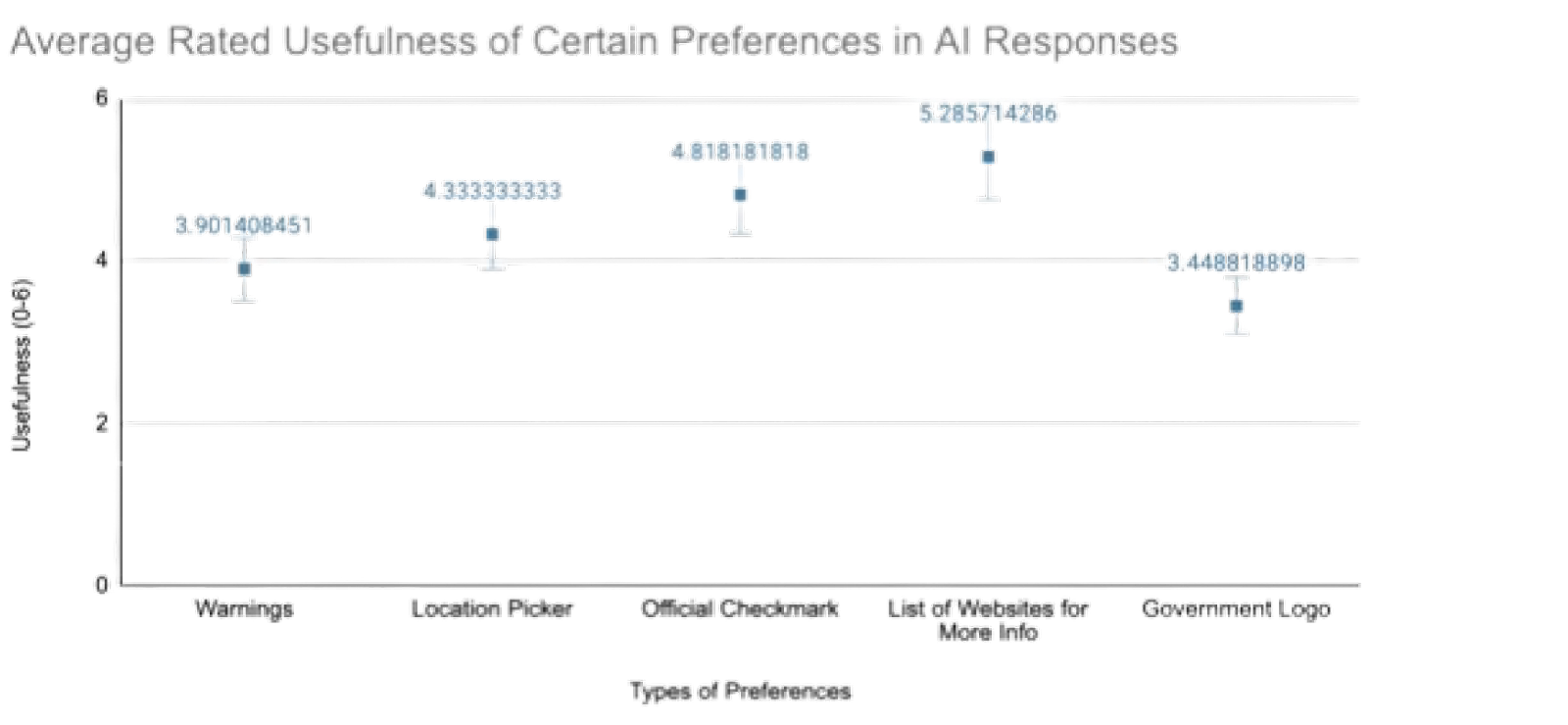

Warning labels are important to AI developers, but they face issues. Consumers often ignore warning labels, and the individuals we surveyed did not seem to see much value in adding warnings. On a scale of 0 to 6, where 0 meant not helpful at all and 6 meant extremely helpful, the surveyed individuals rated warning labels at 3.9 on average.

Current warning labels could therefore use some improvements, and better warning labels could even capitalize on AI’s benefits.

At a minimum, better warning labels should get users’ attention and help them identify potentially inaccurate information. Based on previous studies, this could be done through 1) using visual design changes that emphasize and boost the warning label and 2) including a label next to potentially inaccurate information or hallucinations. These changes could help draw users’ attention to situations in which they should exercise more caution, which would also build their AI literacy and minimize the risk associated with AI’s use for legal help.

To capitalize on AI’s benefits, a warning label could help serve a triaging function by alerting users to the severity of their situation, then channeling them to attorneys or other relevant resources. This could take the form of additional follow-up questions based on certain trigger words that might indicate a more serious legal situation, like “served” or “court date.” In response to trigger words, the AI tool could prompt the user with relevant follow-up questions like, “what happens if I miss my court date?” or “do I need an attorney in court?” Research has found that warnings in the form of prompts or other “visceral behaviors” can be a more effective way at getting users to heed warnings. Moreover, these warnings could help users perform a sort of self-triage in which they understand the severity of their legal situation and can go to a legal aid organization with more knowledge.

Idea 3: Changes to User Interface

Finally, changes could be made to AI tools to improve the user experience. Based on user experience interviews and the preferences and needs of AI users, we identify four key user interface changes: 1) improving accessibility, 2) providing more precise information, 3) increasing avenues to verify information, and 4) increasing length and styles of interaction. Hopefully, with this design-focusing thinking, AI platforms can improve user experience and quality of service to meet users where they currently are amidst these early stages of AI usage and deployment.

Improving Visual and Auditory Accessibility

First, the user interface change that is of foremost importance is the improvement of accessibility. This idea was presented by the interviewed users themselves, suggesting both visual and auditory improvements. For those with visual impairments, there should be an additional option to include non-text information to supplement responses, particularly the inclusion of videos and images. One user stated, “When I did look up AI tools, it was a lot of words so maybe mixing it up with videos and sources to reach out like numbers to call.” (Q5.7; P41)

For those with hearing impairments, there should be the additional option to have information spoken aloud and microphone access for voice commands to engage with the AI chatbot completely auditorily. One user stated, “The option to read it to you, so you can almost be listening and multitasking at the same time. Because some people don’t want to read or can’t read that good, and not comfortable reading.” (Q5.7; P38)

Addressing this accessibility gap within AI chatbots should hopefully encourage a larger variety of users to start interacting with these AI services and increase access to justice.

Providing More Precise Information

Based on user responses to prompted questions, tools should be embedded within the user interface that provide users with pathways to receive more tailored and accredited information. Particularly, two highly rated preferences were: the inclusion of a location picker and an official checkmark to verify information.

The average usefulness rating for a “location picker to tell the tool where you are” was 4.8 out of 6. (Q4.8_4) This additional tool would nudge users to share the location (i.e. the state and county) where the legal challenge is based, which helps provide more tailored legal information. The average usefulness rating for an “official checkmark to confirm that information has been approved by experts” was 4.3 out of 6. (Q4.8_5) This icon would reduce user concerns of hallucination by having legal experts review and approve common AI chatbot responses. From this additional step, AI services can indicate to the user when the generated response corresponds to this previously approved information.

Lastly, the user preference for a “government logo next to information that was taken from official government websites” was perceived as only moderately useful with a rating of 3.4 out of 6. (Q4.8_7) Thus, it is important that users are provided with the ability to get more precise and accredited information to improve both the usefulness of the tool and the overall user experience.

Increasing Avenues to Verify Information

Without backend resolutions of hallucinations, more features should be embedded into the user interface to encourage users to double-check the information provided.

One such feature could be adding icons that lead to an automatic internet search that runs parallel to the AI chatbot response. This feature would allow users to compare results side-by-side. Currently, Bard offers this feature, but based on our preliminary research, this icon is greatly underutilized, with no users interacting with the feature during our supervised AI interactions. Thus, this feature should have a more intuitive design, so users understand how to best utilize this icon, and other platforms should add the icon as well.

A second method of verifying information is embedded hyperlinks within the AI-generated response. Hyperlinks to verified websites with more information can increase users’ fact-checking of the source behind the chatbot’s response. Bing’s AI tool offers this feature, and in interviews, users said including hyperlinks would be extremely helpful to their use of the tool. “I like it. It would be great if they included links, websites, or other things that I could visit for additional information.” (Q3.6; P37)

The third avenue to verify information was including “list of websites to visit to get more information.” (Q4.8_6). This improvement received the highest average usefulness rating of 5.3 out of 6. Users liked having the ability to explore these additional avenues to verify information beyond the AI-generated response with one such user stating “Give more options, especially to visit other websites, links, or directions.” (Q4.7; P37) Although our study did not ask specifically about the usefulness of citations, the addition of this tool, which is currently available on Bing Chat, would likely also be a beneficial option for AI services to include. Therefore, in lieu of actual accuracy improvements and hallucination reductions, these additional avenues for verification are vital for the tool to remain useful as well as ensure that users have an appropriate level of trust in the information provided.

Increasing Length and Styles of Interaction

Changes could be made to the user interface to increase the length of user interaction with the AI chatbot and the number of writing styles that AI chatbot can engage in.

This idea builds upon the model utilized by Bing Chat. Based on our study, the average number of prompts inputted by users was only 1.6, which reflects the need for improvement in the user experience. Following the user’s initial prompt and the AI-generated response, the chatbot should provide multiple suggestions for follow-up prompts to allow the user more easily and effectively continue exploration of a topic or clarify their previous question. As one user stated, “Maybe have like ‘are you looking for…a, b, or c.’ (Q4.7; P41)

A multi-prompt conversation between the user and AI would hopefully increase the variety and quantity of information provided by the AI for a given subject. This should provide a more comprehensive view of the subject to compensate for potential misunderstandings on the AI’s interpretation of an indirect and vague user prompt, as well as, provide avenues for exploration of more specific questions regarding a general topic, which can be helpful to those still learning more efficient query formats. Lastly, although our study did not examine Bing Chat’s different conversing style options, based on the varying user preferences for information format, this ability to customize the user’s chat style would likely be popular. These different chat styles could include options such as conversationally casual, simplified, balanced, precisely detailed, or expertly advanced. Providing suggested prompts and further writing style customizations could keep users more engaged with the AI chatbot and ensure that different user types are more equally able to interact with these AI services.

Ideas for Stakeholders

The sections above highlight potential contributions from technology companies, but the we have also identified several questions that warrant further investigation by key stakeholders, specifically by courts, legal aid groups, and/or universities. Future research on the questions below could help stakeholders take actions to improve the use of AI for access to justice.

In particular, legal aid groups represent a significant group of interest for future research. We wonder how these groups can strategically integrate AI technology to improve internal services, streamline workflow efficiency to produce higher quality service, and allocate more time to handle more cases. One possible solution to these questions is the creation of their AI models catered towards the need of their specific firm trained with the website’s information. These models can triage intake based on urgency or an individual’s legal capability. Each legal aid group can define these parameters, specifying what an urgent case entails. This process can also rank cases in the order of importance or further categorize cases to be sent to lawyers specializing in certain areas.

Furthermore, research on the regulatory strategies that agencies, bar associations, or other governmental agencies employ are essential. How effective are these regulatory approaches? How can state regulators play a pivotal role, and can leading examples, like California, influence other states by passing their own legislation? Addressing AI legal-help concerns is important, but there is ongoing debate for if it is too early for regulatory frameworks to be proposed and implemented, or if regulations should be formulated proactively.

Ideas for Future Research

Further Interviews with Participants

Our first hope would be to conduct more interviews. When conducting more interviews with a similar structure, we hope to incorporate the following populations into the study: people in courtrooms who are from richer or counties in California, individuals already actively seeking help from legal aid organizations, individuals working at legal aid organizations or pro bono lawyers, and courtroom staff helping individuals resolve their legal problems.

As most of our research participants were from Santa Clara County, we wonder if an individual’s geographic location or socioeconomic status impacts their awareness of generative AI. While we have data showing trends for those of various financial backgrounds, Santa Clara’s proximity to tech companies may lead to higher possibilities of exposure. Although our study included a question of what “next steps” would look like after using ChatGPT, it is unclear if these individuals have actively sought out resources from legal aid organizations in the past. Since many individuals seemed to be familiar with the housing scenario from the prompt and have commented on being in similar situations, this can be an additional question asked in future interviews to establish what their current plans would look like before mentioning generative AI tools. The last two categories of individuals focus on those who often meet clients that require legal assistance. It could be interesting to observe if they have a higher likelihood of suggesting AI tools in comparison to Internet searches or if they, too, are not aware of the impact of AI on the legal system.

Moreover, we hope to follow up with current or future participants to observe the current impact of AI chatbots, specifically if individuals are continuously using the platform months after their initial exposure and if their interactions with AI have changed. This follow-up study could specifically focus on those with subsequent legal issues, but this may potentially limit the participants who are rolled over into this second study.

Expanding the Type of Interview

Our interviews were conducted with individual users, but future interviews could be conducted in a group setting. Rather than explaining what these AI tools are, we suggest a more behavioral interview style to replicate what the user experience may be like when participants are first exposed to such tools. There may be guidelines to first log into each platform, but there will be no further instructions to gauge the participants’ level of expertise with technology and legal matters. On the other hand, we hope to conduct interviews with experts and professionals in the field, as shown in the divisions below.

Conclusion

Our study explores the use and application of Generative AI tools in providing legal assistance. Overall, while Generative AI platforms offer exciting room for opportunity and transformation in the legal aid space, ultimately, such tools cannot replace lawyers. A majority of participants were unfamiliar with the tool, and even following their interactions with the tool, very few users reported that they would continue with the platform. However, there were still noticeable benefits in using the platform. Users expressed satisfaction with the tool and participants responded positively to its ease of use, increased accessibility, and low cost. With the rapid expansion of these tools, it is clear that AI platforms will continue to be utilized, like other new technologies, in the context of legal assistance.

We offer several points of guidance for various stakeholders. Platform developers and regulators should seek to better their products by implementing more informative or visually striking warning labels, incorporating various visual and auditory elements to increase accessibility, increasing avenues to verify information, and providing follow-up suggestions to better tailor precise information. Future research can look to conduct a greater number of interviews from diverse backgrounds and a longitudinal study to better assess the long-term impact of these tools and whether trust levels and reliance differ as time progresses.