via In Cuyahoga County, you’re much more likely to get a plea deal if you’re white | cleveland.com.

Why did Kevin McFaul, white and the son of the county sheriff, get off with a misdemeanor conviction last year in his cocaine-possession case — potentially preserving his law license — while Mercia Cherry, a black resident of Cleveland’s East Side, had to take a felony in hers?

Especially considering that their offenses were roughly equivalent and McFaul’s history was spottier.

Why were white out-of-towners Richard Roby, Jason Haffa and Christopher Bonnacci sent home from the Cuyahoga County Justice Center with a misdemeanor slap on the wrist when all of them were caught with more illegal drugs than black visitor Marquita Brewer, who had to drag a felony record back home to Florida with her?

Why was white Cleveland resident Brian Duvall allowed to plead guilty to a misdemeanor after he was pulled over and caught with a vial of powder cocaine dangling from his car keys . . .

Or Robert Hill, a white Lake County resident, who was seen by undercover cops on Cleveland’s East Side buying crack cocaine that was later recovered from his car?

Even though Deloris Smith, a black East-Sider, was saddled with a felony after a piece of steel wool with traces of previously smoked crack was found on the seat of her car, which police had stopped for suspiciously circling a block where drugs are sold.

These cases are among hundreds examined by The Plain Dealer in a months-long effort to gauge the impact of race on how defendants are treated in low-level drug cases in Cuyahoga County.

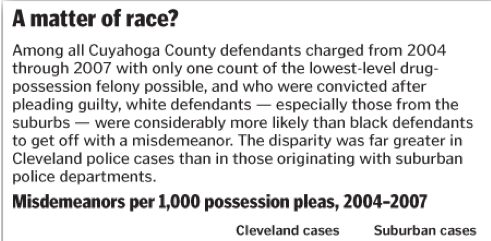

The newspaper reported Sunday that among first-time offenders who pleaded guilty last year to a single felony drug-possession charge, white defendants were 35 percent more likely than black people to get a second chance to make their pleas and charges disappear by successfully completing a treatment plan.

Court records show that virtually all of that racial disparity occurred in something called the Early Intervention Program, the control of which remains somewhat mysterious.

Judges and defense attorneys said in interviews that the program has come to be controlled by Prosecutor Bill Mason’s office over the years, an assertion prosecutors dismiss.

They say it’s a court program, with eligibility determined by the probation department and the decision on who gets in made by judges.

But there is no denying the key role prosecutors play in charging people with felonies — or bargaining a felony charge down to a misdemeanor, a much less serious blight on a person’s record.

Offering plea deals, even though they can ultimately be rejected by judges, is the sole prerogative of prosecutors.

And, according to the Plain Dealer analysis, white defendants appear to enjoy a significant advantage over black defendants in that realm as well.

Among all defendants indicted in Cuyahoga County on a single, low-level drug-possession charge over the last four years who were convicted after pleading guilty, white people were 55 percent more likely than black people to have their charges reduced to a misdemeanor. In most cases, it was to something called “attempted” possession of drugs, even when records indicate the defendant had the drugs and there was nothing “attempted” about it.

Even among those making their first appearance in Common Pleas Court in at least 15 years, white people were 40 percent more likely than black people to get a misdemeanor. Among those with no prior convictions here, whites were 27 percent more likely.

Mason’s top lieutenants said that those numbers could be skewed by the fact that hundreds of Cleveland drug cases — most with black defendants — are diverted with the prosecutor’s blessing to the Greater Cleveland Drug Court, where they are handled as misdemeanors.

Even accounting for Drug-Court data supplied by prosecutors, however, white defendants are still about 45 percent more likely than black defendants to be granted a misdemeanor plea.

Out-of-town or suburban white people enjoyed an even greater advantage in Cleveland cases, according to the Plain Dealer analysis. They were at least 77 percent more likely than black defendants to escape the Justice Center with only a misdemeanor conviction.

Prosecutors say that race and geography have absolutely nothing to do with decisions on charges filed or pleas allowed. And, they argue, there are so many variables in criminal cases that it may be impossible to compare them statistically.

It’s true, an array of factors contributes to the outcome of individual cases — some of which could not be accounted for in the data. Prosecutors note the widely varying facts, circumstances and quality of the evidence in each case — not to mention the criminal histories of thousands of defendants. Add to those the competence and motivation of hundreds of defense attorneys, the even-handedness of dozens of prosecutors and the competence and philosophies of the county’s 34 Common Pleas judges.

In any system with that many human and factual variables, attorneys and judges said, consistency is a tough goal to reach.

The sheer number of drug cases, necessitating a near assembly-line approach to move them along, complicates the equation further.

More than 18,000 drug convictions were handed down in the Cuyahoga County Justice Center in 2005, 2006 and 2007 — an average of two dozen on each and every business day over that period. More than 98 percent of those were the result of guilty pleas and practically all were for felonies.

But on the lower end of the seriousness scale, several hundred misdemeanor pleas have been allowed in drug cases during that span as well. And the facts don’t always square with the outcomes.

A study in contrasts

Mercia Cherry and Kevin McFaul are a study in contrasts.

Cherry was a passenger in a gold Chrysler stopped by Cleveland police for a routine traffic-light violation one spring evening last year at East 124th Street and Kinsman Road.

The driver, a relative of Cherry’s, was arrested on an outstanding warrant.

But Cherry had done nothing. She was not a repeat offender, according to court documents, and had no record to speak of — just minor traffic offenses from years earlier.

Still, police patted her down and said they asked for — and received — permission to search her purse “for weapons.”

Inside Cherry’s purse, police found a camera case. Inside the camera case, they found a brown bag. Inside the bag, they found a wadded paper towel. Inside the towel, they found a metal pipe. Inside the bowl of the pipe they found traces of smoked cocaine. Cherry was charged with felony drug possession.

She blew a chance to have her case diverted to Drug Court by missing two drug-assessment appointments. And because of Cherry’s personal circumstances, the Early Intervention Program was not a workable option, said public defender Robert Tobik, whose staff represented Cherry because she could not afford to hire her own attorney.

But given her lack of priors and the minuscule amount of drugs involved, Cherry was a good candidate for a misdemeanor plea, Tobik said.

He has been arguing for years that more entry-level drug offenders should be allowed misdemeanor pleas, especially in crack-pipe “residue” cases like Cherry’s, which typically involve mere chemical traces of cocaine.

These residue cases clog the system and waste the court’s resources, Tobik said; several judges have made similar arguments. But to no avail: Misdemeanors have actually become harder — not easier — to come by in Common Pleas Court.

Even though the number of defendants pleading guilty to drug possession is up in recent years, according to court data, the proportion getting off with misdemeanors has plummeted: roughly 25 percent of those defendants got misdemeanors from 2000 through 2003, but only about 9 percent ever since.

Cherry was not among them.

With early intervention not an acceptable option, Cherry pleaded “no contest” to the felony charge. Prosecutors said she never even asked for a misdemeanor.

But that’s not true, according to public defender Mary Cay Tylee, who said she pushed prosecutors hard for a reduced charge on Cherry’s behalf.

“I asked the prosecutors to . . . give her a misdemeanor,” Tylee said. “They came back and said, ‘No.’ I asked them to re-review it with some more information from my client and they still said, ‘No’.”

Finally, in August of last year, the 44-year-old Cherry joined the growing ranks of Cuyahoga County drug felons.

Just three months earlier, Kevin McFaul was allowed to plead to a misdemeanor, after his hired attorney asked prosecutors for a charge reduction.

Unlike Cherry, however, McFaul was not a first-timer –although it would have been hard to tell from court records because McFaul caught a break in an earlier case as well.

In 2002, when he was 44, McFaul was arrested after investigators watched him buying crack at East 82nd Street and Bellevue Avenue in Cleveland and then stopped his white Cadillac STS.

Both McFaul and the man he was with told police in tape-recorded statements that McFaul had purchased $30 worth of crack cocaine and then swallowed it when police pulled him over.

No record exists of any charges in that case. Sheriff’s Capt. Michael Jackson, who made the arrest, said he witnessed McFaul admitting his guilt before Municipal Judge Larry Jones, who presides over the Greater Cleveland Drug Court.

Defendants deemed eligible for Drug Court can have their cases dismissed and erased from the public record — without ever going through Common Pleas Court — if they successfully complete the program.

Neither Drug Court officials nor prosecutors would confirm or deny that that’s what happened to McFaul after his 2002 arrest.

But the attorney was arrested again for felony drug possession in late 2006, after county deputies developed what appeared to be open and shut evidence that McFaul bought and consumed at least $40 worth of crack cocaine — far more than Cherry had when she was arrested.

On Oct. 14, 2006, the investigators witnessed McFaul buying crack from a dealer and the dealer’s girlfriend in a Nissan Maxima outside McFaul’s former home in Euclid.

Police got statements to that effect from both the dealer and the girlfriend and they recovered $40 in marked money from the pair that McFaul had used in the purchase. The money had been provided to McFaul earlier by a police informant posing as a potential legal client. After obtaining a search warrant, investigators also found a metal push rod used for crack smoking in the McFaul residence that tested positive for crack residue.

McFaul was indicted on two counts of felony drug possession.

But on the recommendation of the prosecutors’ office, one was dismissed, and the other reduced to a misdemeanor before McFaul pleaded guilty in May of last year to “attempted” possession of drugs.

Prosecutors note that McFaul was placed on five years’ probation, meaning he still could face six months in jail if he fails random drug testing required by the sentence.

Had McFaul been convicted of a felony, however, his law license would have been suspended by the Ohio Supreme Court, pending an investigation into whether he should be further disciplined — up to and possibly including disbarment.

White suburbanite gets an edge

On the matter of misdemeanor pleas, prosecutor protests notwithstanding, it appears from the data to help if you live in the suburbs or outside the area.

It helps even more if you’re from out of town and white.

Richard Roby, for instance, a white resident of eastern Lake County, had driven his silver Pontiac Grand Am to Cleveland’s East Side in July 2004 in search of some action.

Roby cruised up to the corner of Euclid Avenue and Green Road and asked a hooker there if she wanted to “get high.” What he didn’t know was that the “hooker” was an undercover Cleveland cop, who then asked him what he had to party with. Roby said he had some crack, then opened the center console of his car and flicked his lighter so she could see.

She did see. Roby was promptly arrested and relieved of one-fiftieth of an ounce of crack — several rocks’ worth. He spent four days in jail and was sent home to Madison, with nothing but a misdemeanor on his record. Roby was indicted for “attempted” drug possession, pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor and was released — all on the same day.

Prosecutors say Roby was a participant in a jail-reduction program that is no longer in operation.

Christopher BonnacciStopped for speeding. Police found marijuana, crack and crack pipe. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

Christopher BonnacciStopped for speeding. Police found marijuana, crack and crack pipe. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

Then there is Christopher Bonnacci, of Youngstown, who was arrested by Cleveland police for speeding on Interstate 90. Officers found marijuana and a crack pipe with cocaine residue in Bonnacci’s breast pocket — which already made his transgression as bad as Mercia Cherry’s.

But police also found three rocks of crack — weighing one-fortieth of an ounce– in the same pocket. The result was indictments on two felony drug-possession charges. At the request of Bonnacci’s attorney, Mason’s office agreed to dismiss one and reduced the other to “attempted” drug possession.

Bonnacci, who is white, pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor and was fined $200, plus court costs, and sent home to Youngstown. Prosecutors said he had no prior convictions.

But neither did Deloris Smith, who is black and had only traces of drugs on her. She got stuck with a felony.

Marquita BrewerApproached by police while asleep in car. Police found PCP-dipped cigarette. Did not get a plea deal.

Marquita BrewerApproached by police while asleep in car. Police found PCP-dipped cigarette. Did not get a plea deal.

So did Marquita Brewer, also black, a former Clevelander visiting from Florida. Brewer was out with a friend in the early morning hours in January of last year. She ended up asleep or passed out in her white Nissan in the parking lot of a McDonald’s near Broadway and Union Avenue.

Cleveland police approached the car, ordered Brewer and her passenger to step out and found a vial of PCP in her friend’s pants pocket and a rock of crack in his coat.

When Brewer got out, police said, a cigarette dipped in PCP fell to the floorboard near her seat. She was charged with felony drug possession for the cigarette.

Smith, of Cleveland, was pulled over last year after plainclothes police saw her car slowly circling an East Side block near Clairdoan Avenue and Jesse Jackson Place.

Deloris SmithStopped by police after slowly circling a city block. Steel wool with crack residue found in car. Did not get a plea deal.

Deloris SmithStopped by police after slowly circling a city block. Steel wool with crack residue found in car. Did not get a plea deal.

Smith’s passenger was found to have a rock of crack in his pocket. But Smith had nothing on her.

A used Chore Boy — steel wool often used as a crack-pipe filter — with crack residue was found on her seat in the car. She also was charged with felony drug possession.

Given the negligible amount of drugs they had and that neither had a criminal record to speak of, both Smith and Brewer appeared to be good candidates for a misdemeanor plea — especially when compared to white offenders like Roby, Bonnacci and Robert Hill.

But they didn’t get that option. Like Cherry, both had been rejected for a second-chance diversion program. But so had Hill. Twice.

Attorneys and prosecutors

In January 2006, undercover Cleveland cops watched near East 185th Street and Villaview Avenue as Hill, a resident of Lake County, made a pay-phone call to a drug dealer later identified as “Slim.”

Robert HillStopped after police saw drug deal. Handed over several rocks of crack. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

Robert HillStopped after police saw drug deal. Handed over several rocks of crack. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

Officers watched as Slim arrived on the scene and saw Hill buying crack cocaine from him from the driver’s seat of his van. After they pulled Hill over, he told them that he had just bought $15 worth of crack and instructed his wife — his passenger — to hand over the drugs. She coughed up multiple rocks.

Hill failed to show up for Drug Court screening and, like Cherry and Brewer, was rejected for that program. Like Smith, he was later denied entry into a second-chance intervention program.

Unlike Brewer, Cherry and Smith, court records show he tested positive for cocaine while out on bond. But he was allowed to plead to a misdemeanor.

Prosecutors said that Hill’s wife “took ownership of this crime” by pleading guilty to a felony.

Asked why Brewer and Smith were not allowed misdemeanor pleas, the prosecutor said their attorneys never asked for a supervisor to review their case files for a possible charge reduction.

Smith’s court-appointed attorney, Martin Keenan, did not return phone calls seeking his views.

But Mark Stanton, who represented Brewer, said the prosecutor’s explanation is no explanation at all. Stanton said he always explores the misdemeanor option with prosecutors in minor drug-possession cases and is typically told it’s not going to happen. At that point in a case like Brewer’s, he said, a “supervisor review” is a waste of time.

That’s simply not true, said Jerry Dowling, chief of Mason’s criminal division, who noted that attorneys can and do appeal charge-reduction decisions all the way up to Mason, if need be.

After reviewing Brewer’s case, Dowling said she probably would have gotten the misdemeanor if Stanton had asked. And he said he was personally offended by something else Stanton said.

“Everybody knows that if you’re a young man or woman from the suburbs, nice family, going to college, you get the misdemeanor,” Stanton said, “while the poor kid from the East Side is saddled with a felony for the rest of his life.”

That’s hogwash, Dowling said. The prosecutor’s office treats all cases the same, he said. “You look at the facts. You look at the [defendant’s] record. You look at can you prove the case.”

Still, Jason Haffa’s case bears an uncanny resemblance to Stanton’s description.

Jason HaffaPassenger in car that went through stop sign. Heroin and paraphernalia found in car. Tested positive for drug use while out on bond. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

Jason HaffaPassenger in car that went through stop sign. Heroin and paraphernalia found in car. Tested positive for drug use while out on bond. Allowed to plead to misdemeanor.

On an October afternoon in 2006, the 20-year-old Lake County resident and a friend were cruising for drugs near East 166th Street and Wayside Road in Haffa’s mother’s Pontiac Grand Prix when the friend, who was driving, rolled through a stop sign.

Cleveland police stopped the car, found a syringe and other “drug-abuse instruments” in the glovebox and a packet of heroin — just purchased around the corner — under Haffa’s seat.

Haffa was indicted for felony drug possession. He was out of jail on bond when the court granted permission for him to take a previously planned vacation with his family to Aruba.

The day before his scheduled departure, however, Haffa failed a drug test and Judge Daniel Gaul revoked his bond and tossed him back in jail.

Haffa’s retained attorney implored Gaul to reinstate his client’s bond — so he could sign up for his second semester of classes at Lakeland Community College — and then asked for intervention in lieu of conviction, which would have spared Haffa a felony record.

While Gaul did restore the bond, he denied the request for intervention. But Mason’s office took care of Haffa’s felony problem.

Like Brewer and Smith, Haffa wound up pleading guilty.

But even though the car was his and the drugs were under his seat, both Haffa and his friend said the heroin was the friend’s. Prosecutors said Haffa gave them a sworn statement “outlining his and his co-defendant’s involvement” in the crime and pledged to complete drug treatment.

They reduced his charge to a misdemeanor — “attempted” possession of heroin.

Marquita Brewer and Deloris Smith are convicted felons today.

Jason Haffa is not.

News researchers Tanya Sams and Jo Ellen Corrigan contributed to this story.